Hans Christian Andersen Biography

Before he achieved global fame as an author of children’s literature on a par with Aesop and the Brothers Grimm, Andersen suffered three decades of toil, isolation and strife. Had it not been for his unwavering determination to become a professional writer, the literary realm may never have been gifted tales such now-timeless as ‘The Little Mermaid’, ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’ and ‘The Ugly Duckling’.

First, you undergo such a terrible amount of suffering, and then you become famous.

This quote, taken from Hans Christian Andersen’s autobiography The Fairy Tale of My Life (1855), could serve as a one-sentence biography of the great writer. Before he achieved global fame as an author of children’s literature on a par with Aesop and the Brothers Grimm, Andersen suffered three decades of toil, isolation and strife. Had it not been for his unwavering determination to become a professional writer, the literary realm may never have been gifted tales such now-timeless as ‘The Little Mermaid‘, ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes‘ and ‘The Ugly Duckling‘.

***

Born in Odense, the third largest city in Denmark, on Tuesday 2nd April 1805, Hans Christian Andersen was the only son of a sickly, 22-year old shoemaker and his older wife. His family were virtually penniless, and Andersen grew up in a one-bedroom house in Odense’s poorest quarter. In his youth, he attended school sporadically, and spent far more time memorizing and reciting stories than studying in any traditional fashion. This propensity for storytelling, combined with the sudden death of his father in 1816, led to Andersen’s mother deciding her eleven-year son needed to learn a proper, wage-paying trade. She sent him to apprentice as a weaver, after which he worked reluctantly in a tobacco factory and a tailor’s shop.

SELECTED BOOKS

In 1819, aged fourteen, Andersen travelled a hundred miles to the Danish capital Copenhagen to seek his fortune. However, his first three years were marked by extreme poverty and a string of failed financial endeavours. At first, having an excellent soprano voice, Andersen was accepted into a boy’s choir, but when his voice began to break he was forced to quit. He then attempted to become a ballet dancer, but his tall, gangly body prevented him from finding any success. In desperation, Andersen even attempted manual labour – a style of work to which he had never been suited. During these three years, following advice given him by a poet he had met while singing in the choir, Andersen began to write, penning a number of short stories and poems.

In 1822, at the age of 17, Andersen’s dogged persistence paid off, following a chance encounter with a man named Jonas Collin. Collin was director of the Royal Danish Theatre, and having read a number of Andersen’s writings – including his first published story, ‘The Ghost at Palnatoke’s Grave’ – felt convinced he showed promise. Collin approached King Frederik VI (1768-1839), and managed to convince the monarch to partially fund the young artist’s education. (In recent times, various other theories pertaining to Andersen’s royal connection have arisen, stemming from both Andersen’s father’s firm belief that he possessed noble heritage, and the notion that Andersen himself may have been an illegitimate son of the royal family.)

READ STORIES

Hans Christian Andersen began his education in the towns of Slagelse and Helsingor, on the Danish island of Zealand. However, despite receiving the finest schooling, he was an average student – possibly because he suffered from dyslexia – and was mocked by other pupils for his desire to become a writer. At one point, he lived at his schoolmaster’s home, where he was physically abused. Andersen would later describe his time in school as the most unhappy period of his life. In 1827, his despair led Jonas Collin to remove him from school, and organise for Andersen to complete his studies in Copenhagen with a private teacher. In 1828, the 23-year old passed the required exams for entrance into the University of Copenhagen.

In 1829, during his first year of university studies, Andersen achieved his first notable literary success with a short story entitled ‘A Journey on Foot from Holmen’s Canal to the East Point of Amager’. During the same semester, he published a comedy and a collection of poems. Four years later, Andersen received a grant from King Frederik for travel expenses, and spent the next 18 months roaming through Germany, Switzerland, France and Italy – the last of which he was deeply fond. For Andersen, this trip began a lifelong infatuation with travel – over the course of his life he would embark on some thirty extended journeys, spending a combined fifteen years of his life in other countries. Indeed, aside from the fairy tales that would eventually cement his fame, Andersen was renowned for his vivid travelogues, and is credited with having declared “to travel is to live.”

In 1835, Hans Christian Andersen published his breakthrough piece of writing – an autobiographical novel titled The Improvisatore. An instant success, the book’s detailing of rural Italy delighted readers all across Europe, and it was translated into French and German within two years of its publication. Also in 1835, Andersen published the first of his now-legendary fairy tales. Despite their modern status, these first efforts weren’t immediate successes, being overshadowed by his next two novels, O.T. (1836) and Only a Fiddler (1837), and his Scandinavianist poem I am a Scandinavian (1840).

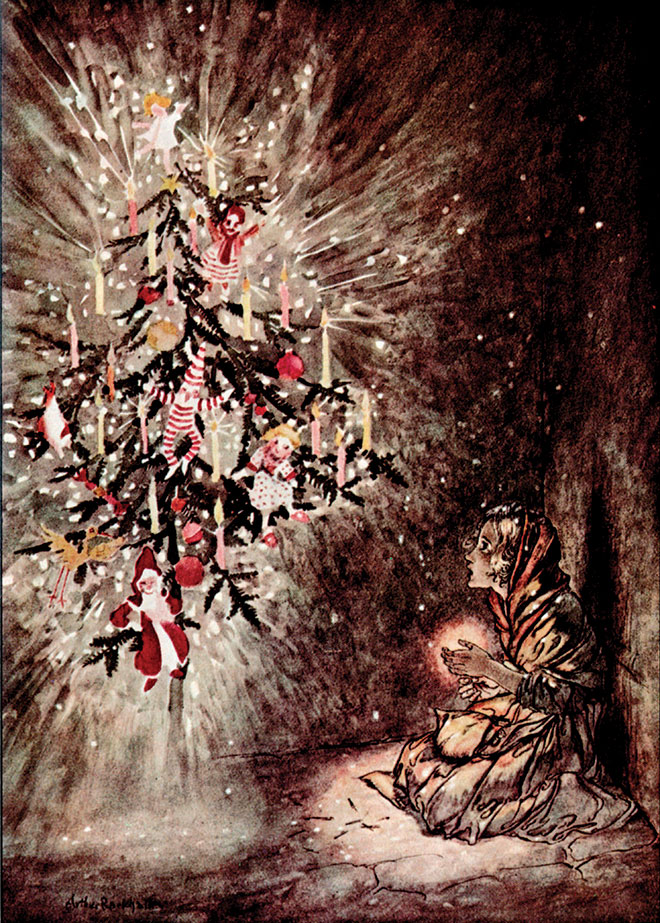

SELECTED BOOKS

The fame of Andersen’s fairy tales (revolutionary in the field of Danish children’s literature) began to grow during the late thirties. Between 1835 and 1837, over three booklets, he published his first collection of stories, which included ‘The Little March Girl‘, ‘The Princess and the Pea‘, ‘Thumbelina‘, ‘The Little Mermaid‘, and ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes‘. In 1838, he published his second series, Fairy Tales Told for Children, which consisted of such well-known tales as ‘The Daisy’, ‘The Steadfast Tin Soldier‘ and ‘The Wild Swans’. Over the next seven years, Andersen continued to regularly publish collections, the 1843 version of which included ‘The Ugly Duckling‘ – cementing his reputation as a leading author of children’s literature. Over the rest of his life, Andersen would go on to publish a total of more than a hundred and fifty fairy tales.

In 1838, the spectre of poverty was banished from Andersen’s life forever, when King Frederick VI awarded him an annual stipend for life. By the 1840s, he was an internationally renowned author, celebrated across the continent for his apparently inimitable storytelling gift. During visits to Germany and England in 1846 and 1847 respectively, he was hailed as a foreign dignitary, and while in London he met Charles Dickens for the first time, returning some ten years later to stay at the writers’ home for five years. In 1846, he received the Knighthood of the Red Eagle from King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, and while in France he spent time with a number of famous artists, including Honore de Balzac, Alexandre Dumas and Victor Hugo. (Interestingly, however, in his native Denmark, the praise for Andersen’s work wasn’t quite so unanimous. Amongst others, the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard attacked his work for being naïve and fundamentally vacuous.)

Hans Christian Andersen spent many of the later years of his life penning well-received travelogues, including his acclaimed Pictures of Sweden (1851) and In Spain (1863). Meanwhile, despite a desire to build his literary reputation on more adult fiction, his Fairy Tales continued to appear in instalments, and to prove extremely popular with readers. The last batch appeared in the spring of 1872, a few weeks before Andersen fell out of bed and severely injured himself. Over the next couple of years, Andersen’s literary output declined, and he developed liver cancer. He died on the 4th August 1875, while in the care of his friends in Copenhagen.

***

It is perhaps curious that a man who never married, and who never had any children of his own, managed to pen tales so well-tuned to the child psyche. Part of the explanation for this may lay in Andersen’s own troubled life. For one, the Dane was denied anything like a proper childhood of his own, with his father dying when he just eleven and his mother forcing him into the world of manual work. Also, Andersen had an odd and in many ways childlike relationship with love and lust. A lifelong celibate, he frequently fell in love with unattainable women – his tale ‘The Nightingale’ was inspired by Andersen’s unrequited love for opera singer Jenny Lind – and also experienced a number of unreciprocated passions for various men in his life. (Tales such as ‘The Little Mermaid‘ and ‘The Ugly Duckling’ play deeply into themes of impossible love and poor self-image.) This self-imposed celibacy, combined with his apparently impassioned bisexuality, has caused much debate amongst Andersen’s biographers. In 2011, a proposal by a number of Danish MPs to instigate a gay pride week in honour of the cherished national poet polarised national opinion.

As an interesting aside, it is worth noting that many of the popular English translations of Andersen’s tales are said to lose much of the deeper – and, in many instances, darker – layers that they possess in the original Danish. The original tales are run through with existential and often pained themes; however, during the 1840s, many of Andersen’s earliest translators simplified the language and bent the tales to suit strict Victorian ideals of moralism and civility, even going so far as to drastically alter features of the plot. It was due in large part to this that, in Britain, Andersen’s tales came to be viewed as simple, sentimental children’s yarns – whereas on the continent they were viewed as much more complex pieces of work. As Andersen himself once stated, in talking about his creative process:

I seize on an idea for grown-ups, and then tell the story to the little ones while always remembering that Father and Mother often listen, and you must also give them something for their minds.

Later, he complained about the reputation his work had garnered in Britain:

I said loud and clear that I was dissatisfied… that my tales were just as much for older people as for children, who only understood the outer trappings and did not comprehend and take in the whole work until they were mature.

Ultimately, Hans Christian Andersen’s tales – originally laced with comedy, social critique, satire and philosophy – have undoubtedly suffered, across various translations and adaptations, from a century and a half of emotional child-proofing. Indeed, no two pieces of work are more guilty of sanitising and sweetening Andersen’s life and work than the sugary 1952 biopic Hans Christian Andersen and Disney’s famous The Little Mermaid (1989) – which swapped Andersen’s original ending (as contained in this collection) for one in which Ariel and Eric marry and live happily ever after.

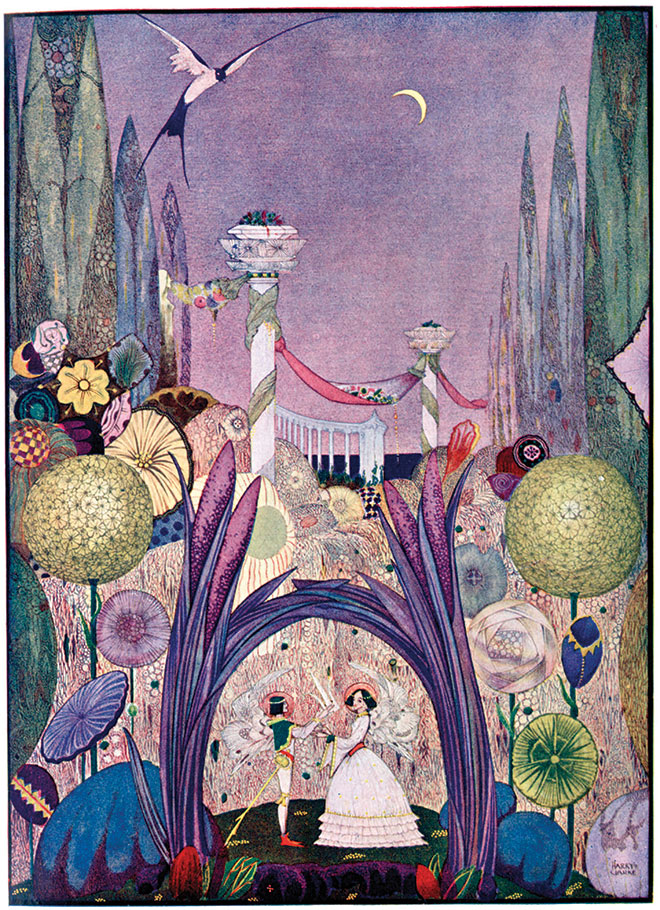

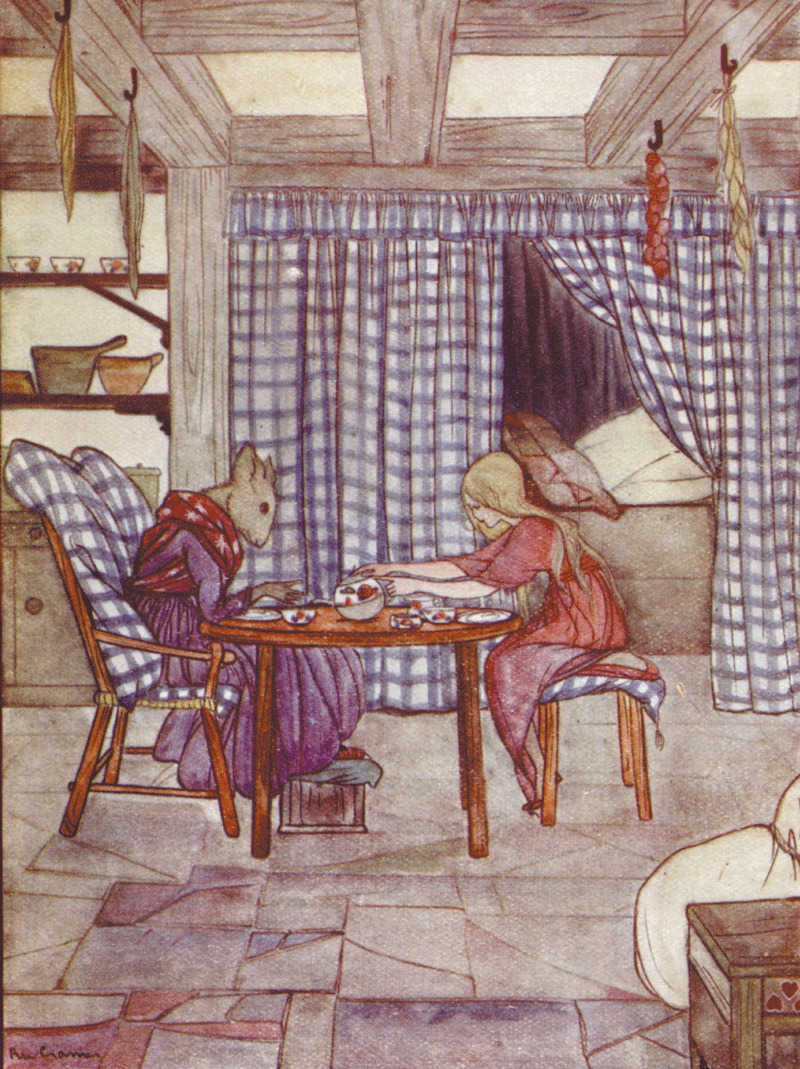

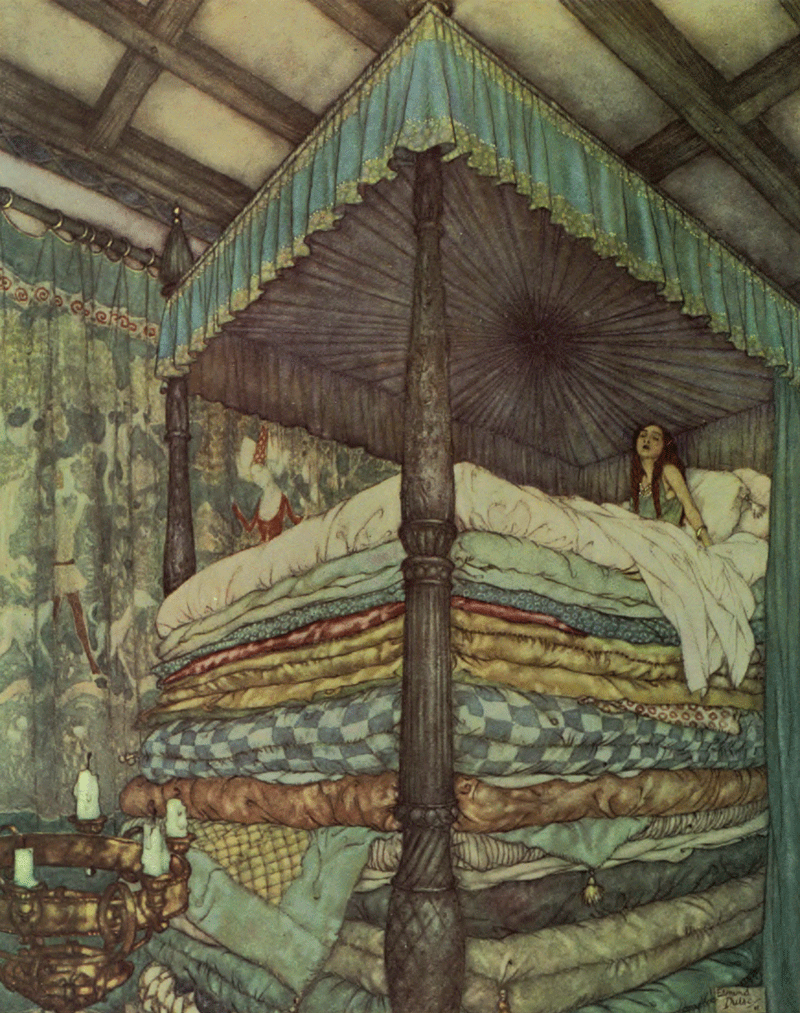

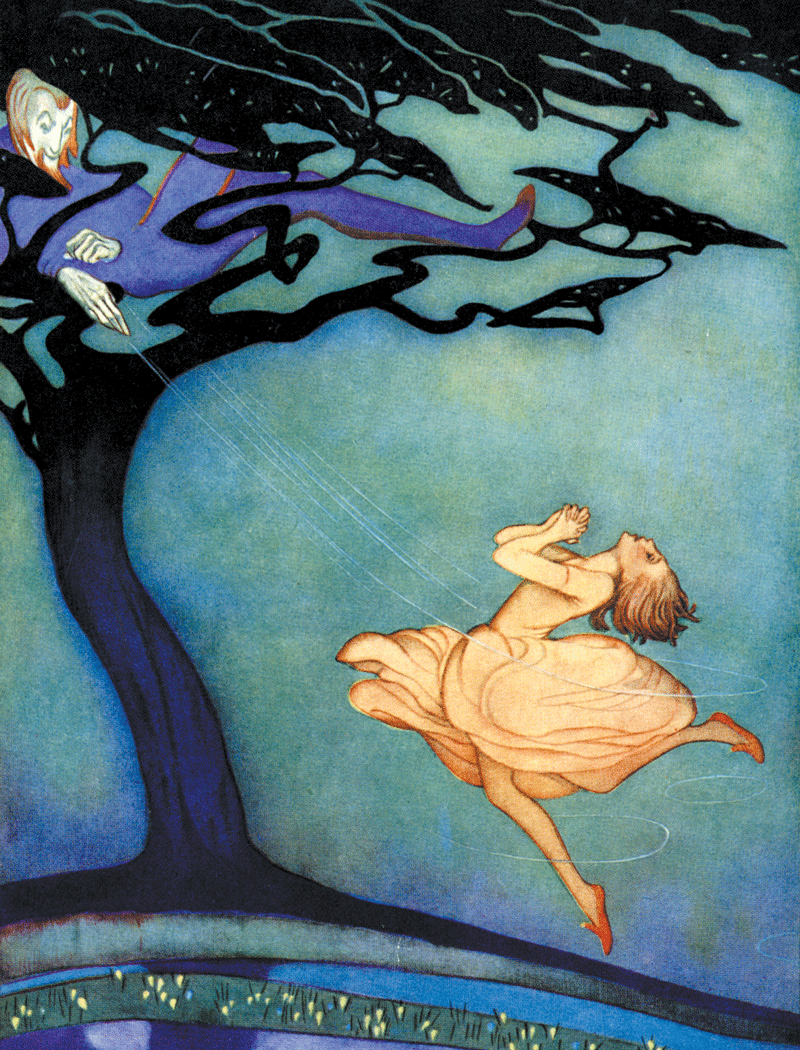

However, the original tales, as contained here, remain stunning pieces of fantastic literature, all beautifully illustrated by some of great artists of The Golden Age of Illustration, such as Arthur Rackham, Milo Winter, Harry Clarke, Honor C. Appleton, Kay Nielsen, Jennie Harbour, and Anne Anderson.

Whatever the facts of Andersen’s psychology and sexuality, and regardless of the existence of less-than-satisfactory translations, there is no doubt that he ranks alongside the Brothers Grimm as one of the greatest authors of children’s literature of all time. His stories have been translated into more than 150 languages – from Inupiat in the Arctic to Swahili in Africa – and have inspired almost countless adaptations (including as theme parks, in both Japan and China). “The Emperor’s New Clothes” and “The Ugly Duckling” have both passed into the English language as well-known idioms, and. International Children’s Book Day has been celebrated on the 2nd April – Andersen’s birthday – since 1967.

Ultimately, however much he might have wanted to be taken more seriously as a writer of adult fiction, Andersen had an exceptional, mercurial relationship with his child readers; a relationship which lasted right up until the weeks before his passing. He informed the composer writing the music for his funeral that:

Most of the people who will walk after me will be children, so make the beat keep time with little steps.

DISCOVER

SELECTED BOOKS