The Snow Queen – Seventh Story

THE SNOW QUEEN – FIRST STORY

THE SNOW QUEEN – SECOND STORY

THE SNOW QUEEN – THIRD STORY

THE SNOW QUEEN – FOURTH STORY

THE SNOW QUEEN – FIFTH STORY

THE SNOW QUEEN – SIXTH STORY

The Snow Queen

A Hans Christian Andersen Tale

– Seventh Story –

Of the Snow Queen’s Castle and What

Happened There at last

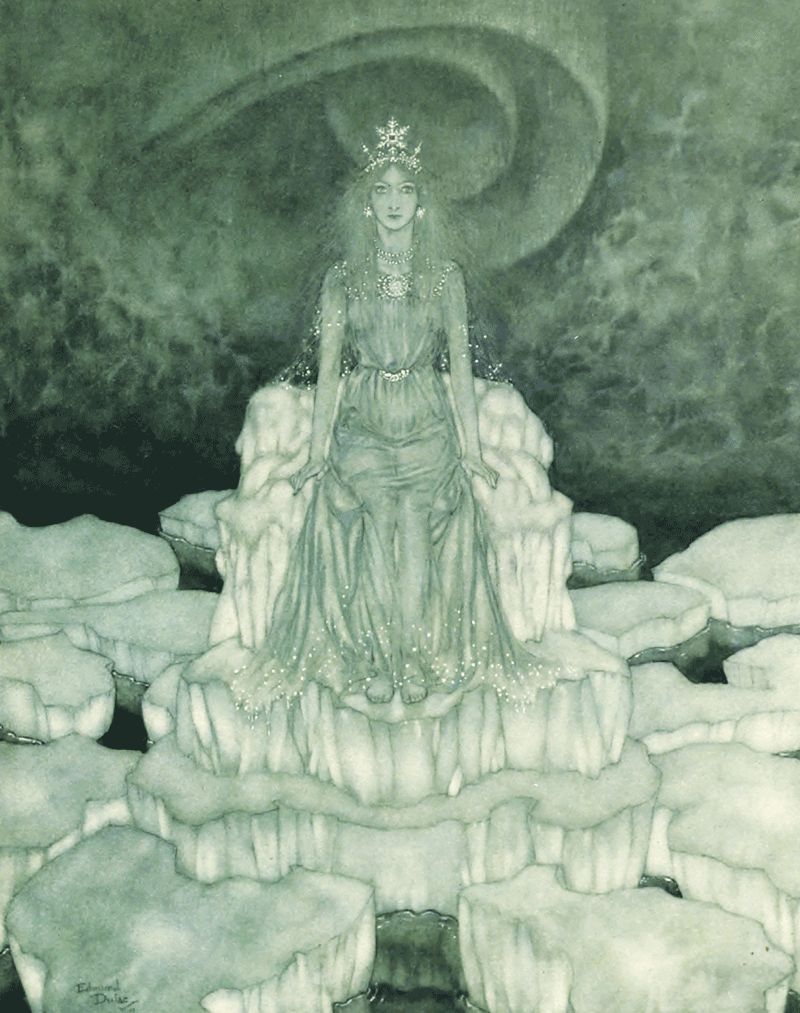

The walls of the palace were made of the drifting snow and the windows and doors of the cutting winds. There were more than a hundred halls, all just as the snow had drifted. The largest of them extended for several miles; they were all lit up by the strong Northern Lights, and how wide and empty, how icy cold and glittering they all were! There never was any merriment there, not even a little bears’ ball, at which the storm could have played the music, while the polar bears walked about on their hind legs and showed off their pretty manners; never any little games of kiss-in-the-ring or touch; never any little coffee parties among the young lady arctic foxes. Empty, vast, and cold were the halls of the Snow Queen. The Northern Lights flamed so brightly that they could be counted both when they were highest in the sky and when they were lowest. In the middle of this empty endless snow hall was a frozen lake. It had cracked into a thousand pieces, but each piece was so exactly like the rest that it was a perfect work of art. In the middle of the lake sat the Snow Queen when she was at home, and then she said that she sat in the mirror of understanding, and that this was the only one, and the best in the world.

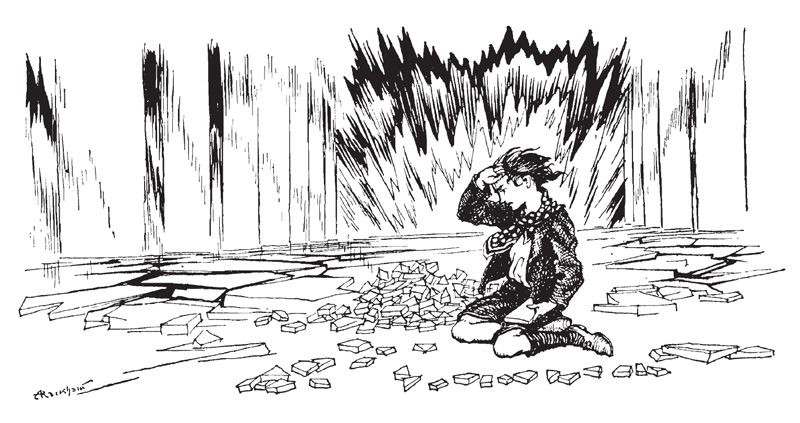

Little Kay was quite blue with cold—indeed, nearly black; but he did not feel it, for she had kissed away his icy shiverings, and his heart was like a lump of ice. He was dragging some sharp flat pieces of ice to and fro, joining them together in all kinds of ways, for he wanted to make something out of them. It was just like when we have little tablets of wood and piece them together to form patterns which we call a Chinese puzzle. Kay was making patterns too—and very artistic ones. It was the ice game of reason. In his eyes the patterns were very remarkable and of the highest importance; that was because of the speck of glass in his eye. He laid out whole patterns, so that they formed words—but he could never manage to make the word he wanted—the word ‘eternity.’

The Snow Queen had said: “If you can make that word you shall be your own master, and I will give you the whole world and a new pair of skates.”

But he could not.

“Now I must fly away to warm countries,” said the Snow Queen. “I will go and peep into the black cauldrons.” She meant the burning mountains Etna and Vesuvius, as they are called. “I’ll whiten them a little. That’s necessary; it will be good for the lemons and the grapes.”

And away flew the Snow Queen, and Kay sat all alone in the great empty mile-long ice hall and gazed at his pieces of ice, and thought and thought till cracks were heard inside him: one would have thought that he was frozen.

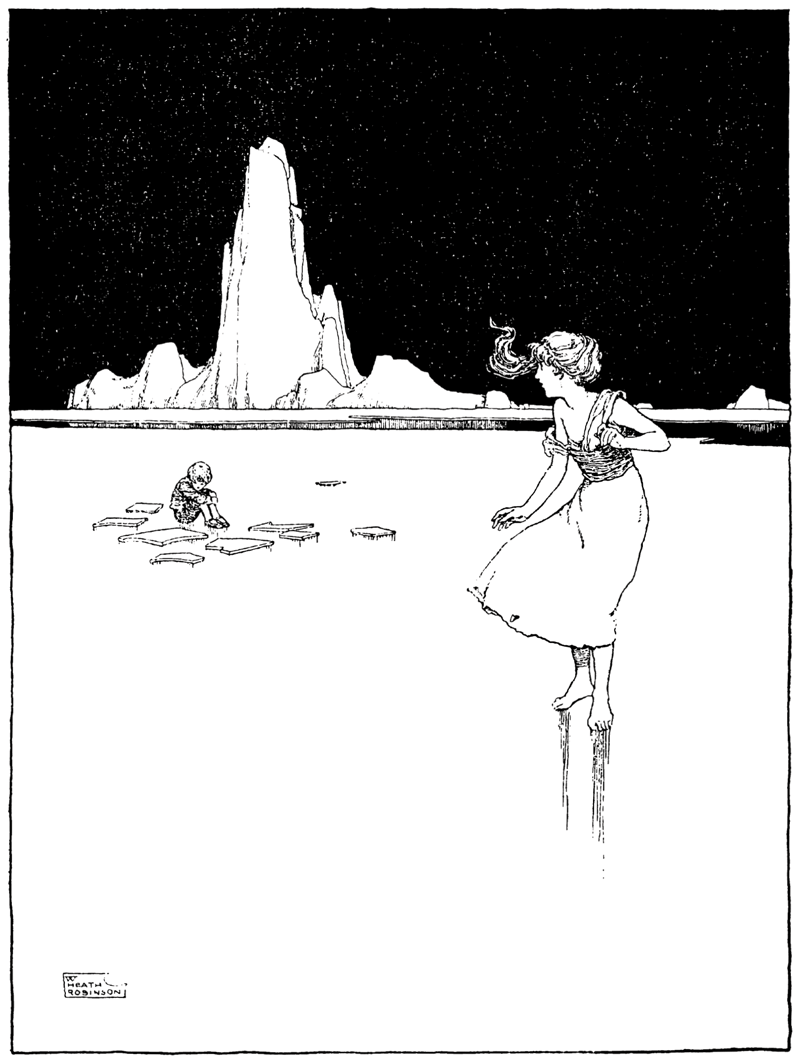

It was then that little Gerda entered the castle by the great gate. Here cutting winds kept guard, but she said the evening prayer, and the winds dropped as if they wanted to go to sleep; and she went on into the great empty cold halls, and she saw Kay. She recognized him, and flew to him, and embraced him, and held him fast, and called out:

“Kay, dear little Kay! At last I have found you!”

But he sat quite still, stiff and cold. Then little Gerda wept hot tears, which fell upon his breast. They penetrated into his heart, they thawed the lump of ice, and melted the little piece of glass in it. He looked at her, and she sang the hymn:

Roses fade and die, but we

Our Infant Lord shall surely see.

Then Kay burst into tears. He wept so that the splinter of glass was washed out of his eye. And then he knew her, and cried joyfully: “Gerda, dear little Gerda! Where have you been all this time? And where have I been?” And he looked all around him. “How cold it is here! How empty and vast!”

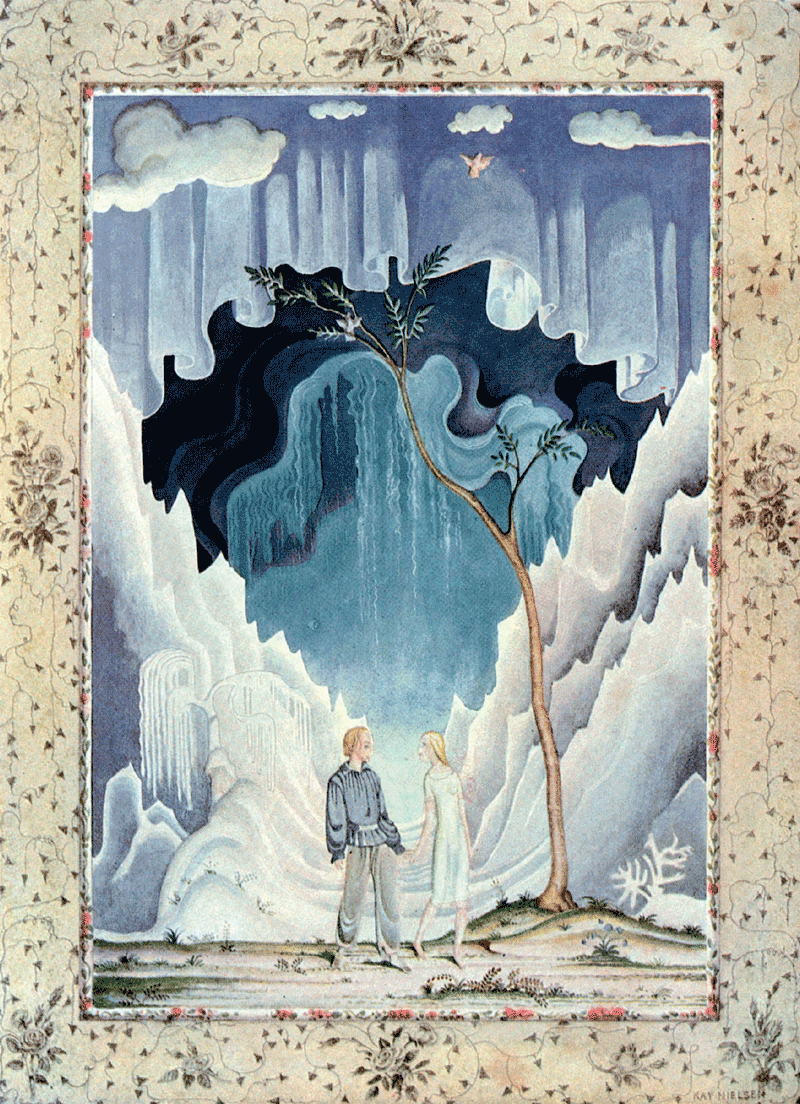

And he held fast to Gerda, and she laughed and wept for joy. There was such joy that even the pieces of ice danced about them; and when they were tired and lay down again they formed themselves into the very letters the Snow Queen meant when she said that if he found them out he should be his own master, and she would give him the whole world and a new pair of skates.

And Gerda kissed his cheeks, and they became blooming. She kissed his eyes, and they shone like her own. She kissed his hands and feet, and he became well and merry. The Snow Queen might come home now; there stood his discharge, written in shining blocks of ice.

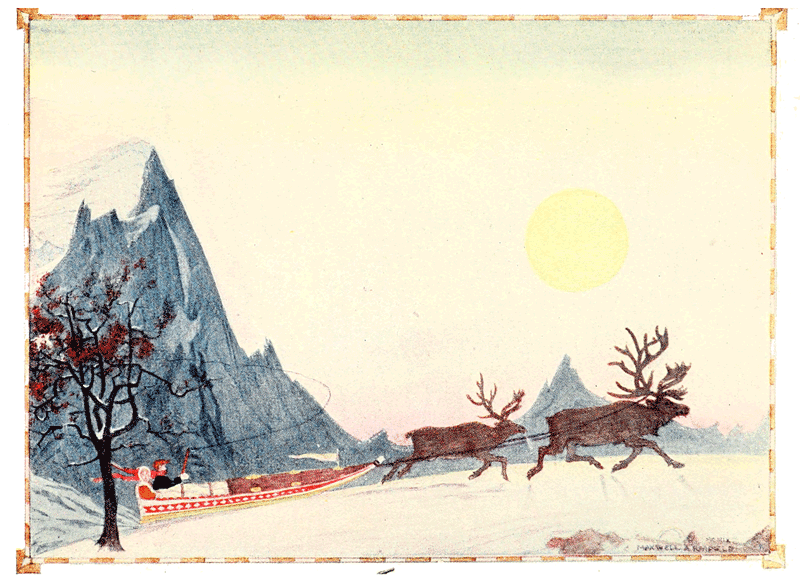

And they took each other by the hand and went out of the great palace. They talked of the grandmother, and of the roses on the roof; and wherever they went the winds sank to rest and the sun came out; and when they came to the bush with the red berries, the reindeer was standing there waiting. He had brought with him another young reindeer, whose udder was full, and who gave the children warm milk and kissed them on the mouth. Then they carried Kay and Gerda, first to the Finn woman, where they warmed themselves thoroughly in the hot room, and received instructions for their journey home, and then to the Lapp woman, who had made clothes for them and got their sledge ready for them.

The reindeer and the young one ran free by their side, and followed them as far as the boundary of the country, where the first green leaves were budding, and where they took leave of the two reindeer and the Lapp woman. “Farewell!” they all said. And once more they heard the birds twitter and saw the forest all decked with green buds, and out of it, on a splendid horse, which Gerda knew, for it had drawn her golden coach, a young girl came riding, with a bright red cap on her head and pistols in her belt. It was the little robber girl, who had grown tired of staying at home, and wished first to go north and, if she didn’t like that, then somewhere else. She knew Gerda at once, and Gerda knew her too; it was a joyful meeting.

“You are a fine fellow to go gadding about!” she said to little Kay. “I should like to know whether you deserve that anybody should run to the end of the world after you!”

But Gerda patted her cheeks, and asked after the Prince and Princess.

“They’ve gone to foreign countries,” said the robber girl.

“But the crow?” said Gerda.

“Why, the crow is dead,” answered the other. “The tame sweetheart has become a widow, and goes about with a bit of black worsted round her leg. She complains most sadly, but it’s all talk. But now tell me how you have fared, and how you got hold of him.”

And Gerda and Kay told their story.

“Snip-snap-snurre-basselurre!” said the robber girl.

And she took them both by the hand, and promised that if she ever came through their town she would come and pay them a visit. And then she rode away into the wide world. But Gerda and Kay went hand in hand, and as they went the spring became lovely with flowers and verdure. The church bells rang, and they recognized the high steeples and the great town in which they lived. On they went to their grandmother’s door, and up the stairs, and into the room, where everything stood in the same place as before. The big clock was going “Tick! tick!” and the hands moved; but as they went in through the door they noticed that they had become grown up people. The roses out on the roof gutter were blooming at the open window, and there stood their little children’s stools, and Kay and Gerda sat down each on their own, and held each other by the hand. They had forgotten the cold empty grandeur of the Snow Queen’s castle like a heavy dream. Grandmother was sitting in God’s bright sunshine, and read aloud from the Bible, “Except ye become as little children, ye shall in no wise enter into the kingdom of God.”

And Kay and Gerda looked into each other’s eyes, and all at once they understood the old hymn:

Roses fade and die, but we

Our Infant Lord shall surely see.

There they both sat, grown up and yet children—children at heart—and it was summer, warm lovely summer.