The Snow Queen – Third Story

THE SNOW QUEEN – FIRST STORY

THE SNOW QUEEN – SECOND STORY

The Snow Queen

A Hans Christian Andersen Tale

– Third Story –

The Flower Garden of the Woman who Knew Magic.

But how did it fare with little Gerda when Kay did not return? What could have become of him? No one knew; no one could give information. The boys could only say that they had seen him tie his little sledge to another very large one, which had driven along the street and out at the town gate. Nobody knew what had become of him; many tears were shed, and little Gerda cried long and bitterly. Then they said he was dead—he had been drowned in the river which flowed close by the town. Oh, those were long dark winter days indeed! Then came the spring, with its warm sunshine.

“Kay is dead and gone,” said little Gerda.

“I don’t believe it,” said the sunshine.

“He is dead and gone,” said she to the swallows.

“We don’t believe it,” they replied; and at last little Gerda did not believe it herself.

“I will take my new red shoes,” she said one morning, “those that Kay has never seen; and then I will go down to the river, and ask it about him.”

It was still very early; she kissed her old grandmother, who was asleep, took her red shoes, and went all alone out of the town gate to the river.

“Is it true that you have taken my little playmate? I will make you a present of my red shoes if you will give him back to me!”

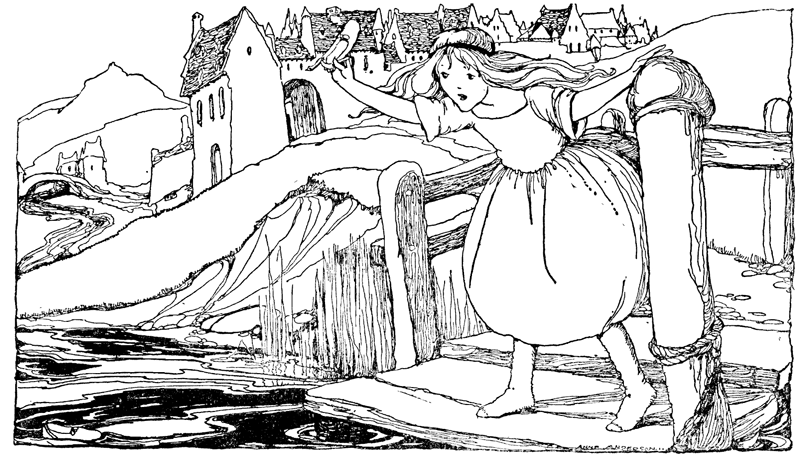

And it seemed to her as if the waves nodded strangely; and then she took her red shoes, that she liked best of anything she possessed, and threw them both into the river; but they fell close to the bank, and the little wavelets bore them back to land again. It seemed as if the river would not take from her the dearest things she had because it had not got her little Kay. But she thought she had not thrown the shoes far enough out; so she climbed into a boat that lay among the reeds, and went to the farther end of the boat, and threw the shoes into the water again; but the boat was not made fast, and at the movement she caused it drifted away from the shore. She noticed it, and hurried to get back, but before she reached the other end of the boat it was a yard from the bank, and was floating quickly away.

Then little Gerda was very much frightened, and began to cry; but no one heard her except the sparrows, and they could not carry her to land. They flew along the bank, and sang, as if to console her, “Here we are! here we are!” The boat drifted on with the stream, and little Gerda sat quite still, in her stockings. Her little red shoes floated along behind, but they could not catch up with the boat, which drifted faster.

It was very pretty on both sides. There were beautiful flowers, old trees, and slopes with sheep and cows; but not a human being was to be seen.

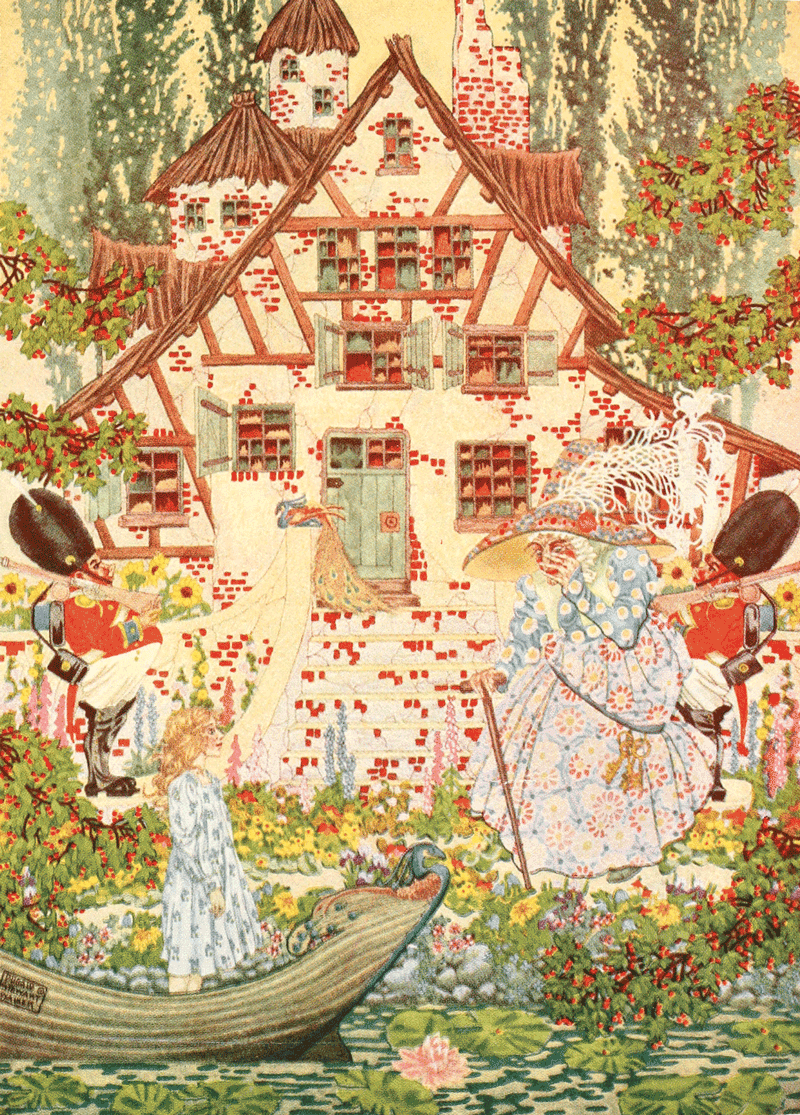

“Perhaps the river will carry me to little Kay,” thought Gerda. And then she became more cheerful, and stood up, and for many hours she watched the pretty green banks. At last she came to a big cherry orchard, where there was a little house with curious blue and red windows. It had a thatched roof, and in front stood two wooden soldiers, who presented arms to those who sailed past.

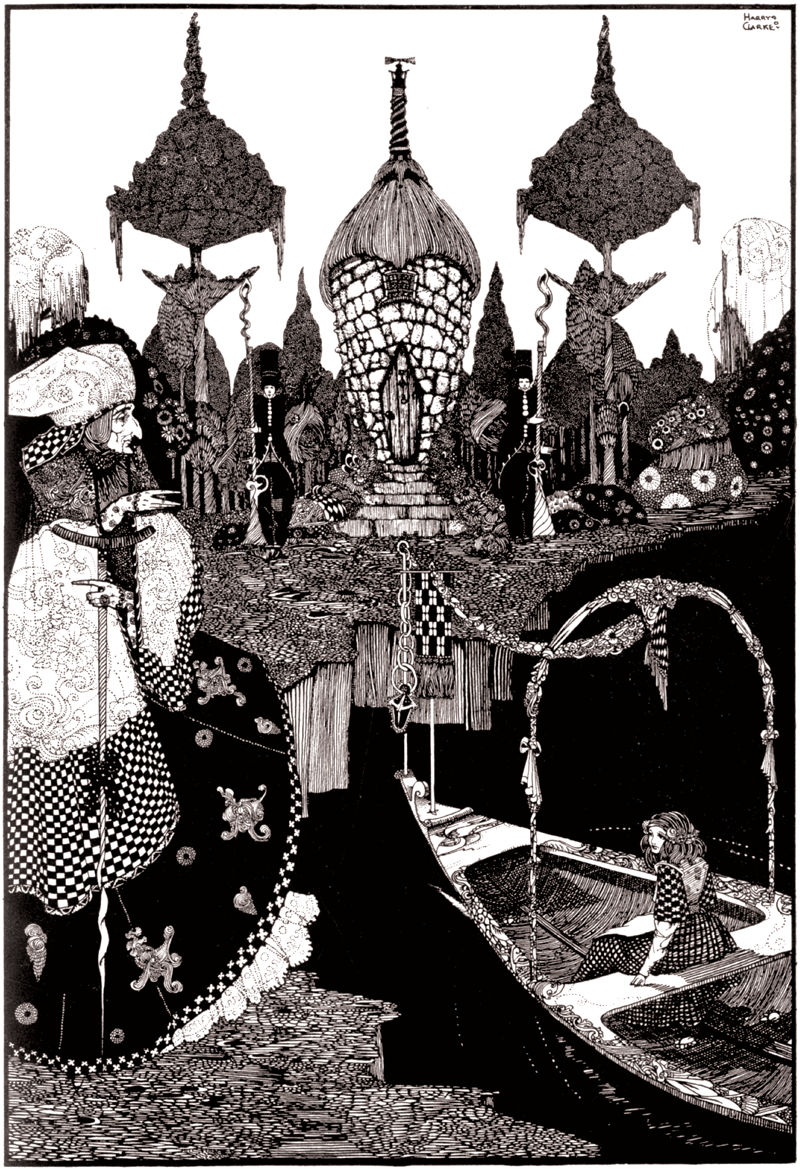

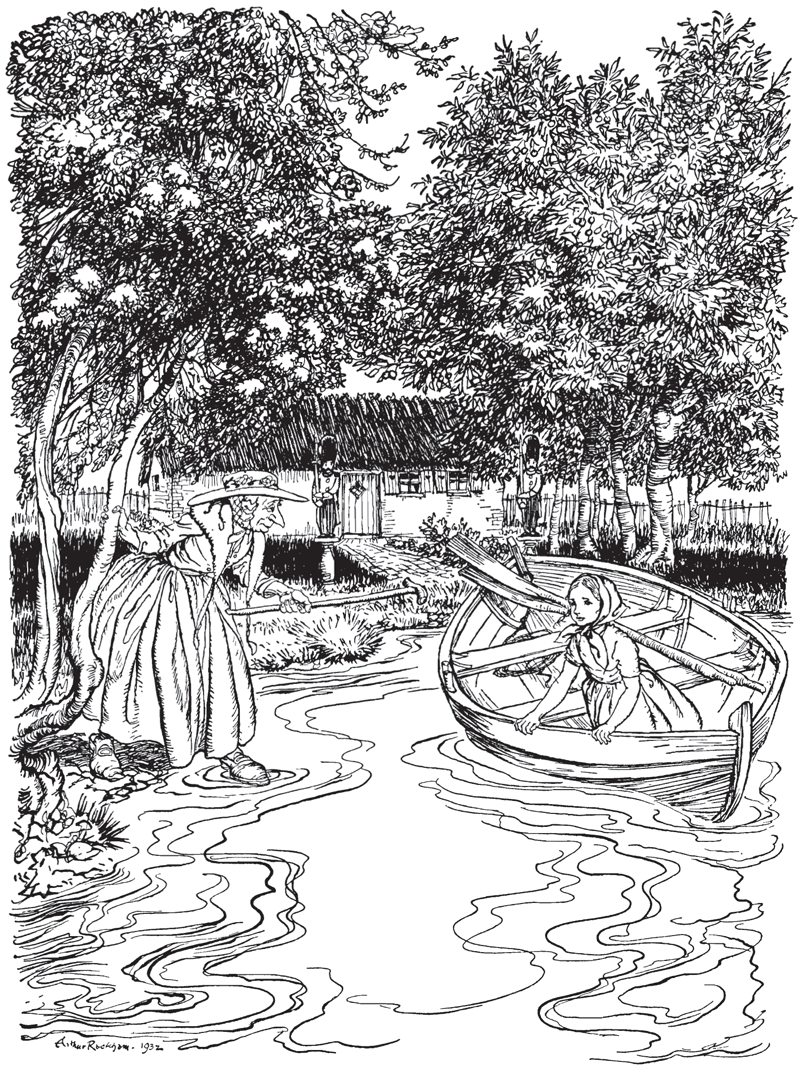

Gerda called to them, for she thought they were alive, but, of course, they did not answer. She came quite close to them; the river carried the boat into the shore.

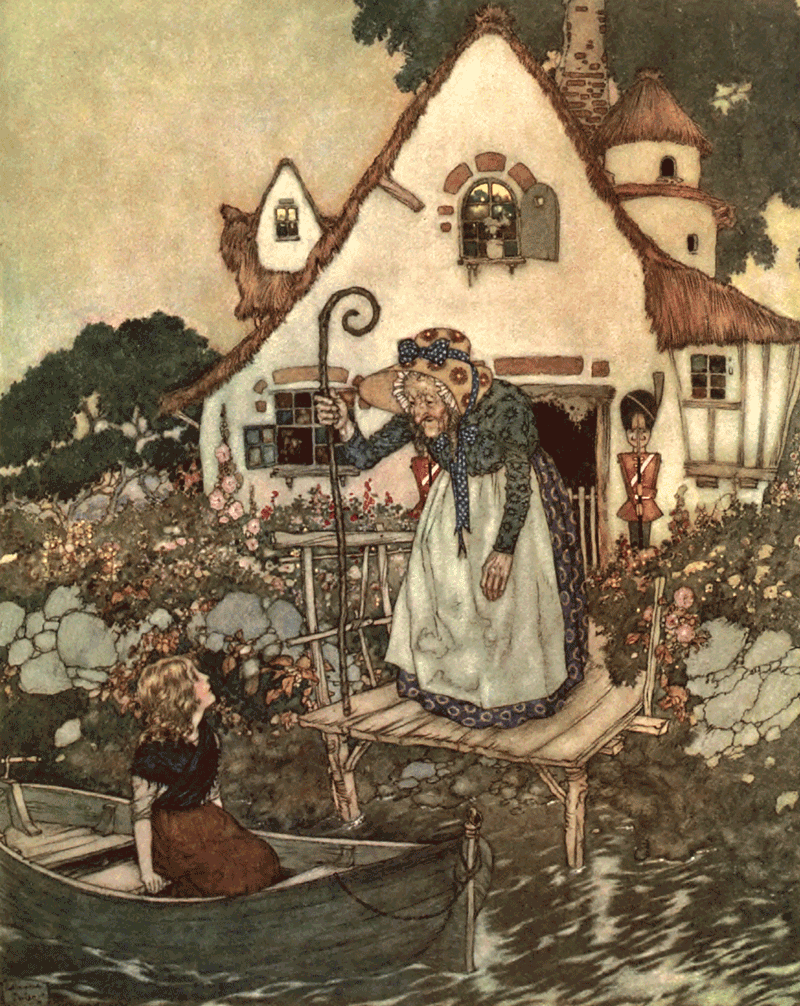

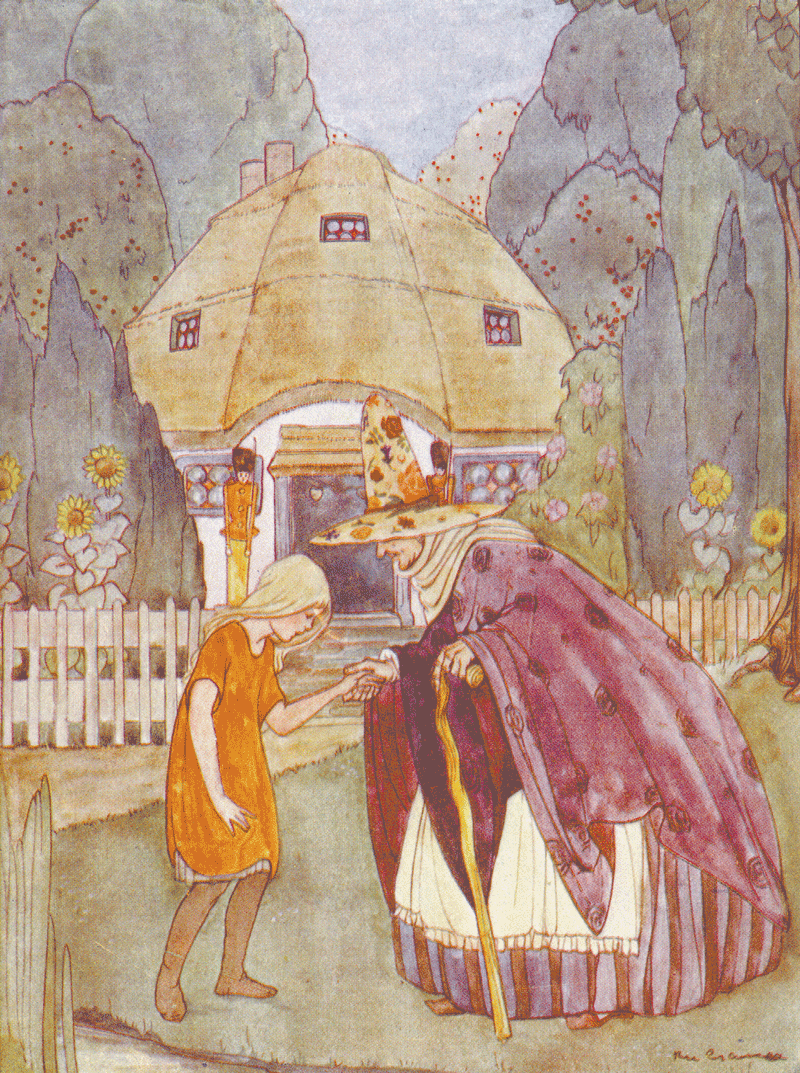

Gerda called out still louder, and then there came out of the house an old, old woman leaning on a crutch: she had on a big sun-hat, painted with the most lovely flowers.

“You poor little child!” said the old woman. “How did you manage to come on the great strong river, and to float so far out into the wide world?”

And then the old woman went right into the water, hooked the boat with her crutch, drew it to land, and lifted little Gerda out. Gerda was glad to be on dry land again, though she felt a little afraid of the strange old woman.

“Come and tell me who you are, and how you came here,” said she. And Gerda told her everything; and the old woman shook her head, and said, “Hm! hm!” And when Gerda had told her everything, and asked if she had not seen little Kay, the woman said that he had not yet come by, but that he probably would soon come; she was not to be sorrowful, but taste her cherries and look at the flowers, for they were better than any picture-book, for each one of them could tell a story. Then she took Gerda by the hand and led her into the little house, and the old woman locked the door after them.

The windows were very high up, and the panes were red, blue, and yellow; the daylight shone in in a strange way, with all colours. On the table stood the finest cherries, and Gerda ate as many as she liked, for she had leave to do so. While she was eating them the old woman combed her hair with a golden comb, and the hair curled and shone like lovely gold round the sweet little face, which was round and as blooming as a rose.

“I have long wished for such a dear little girl as you,” said the old woman. “Now you shall see how well we shall get on together.”

And the more she combed little Gerda’s hair, the more Gerda forgot her playmate Kay; for this old woman could work magic, but she was not a wicked witch. She only practised a little magic for her own amusement, and now only because she wanted to keep little Gerda. So she went into the garden, stretched out her crutch towards all the rose-bushes, and, beautiful as they were, they all sank into the black earth, and no one could tell where they had stood. The old woman was afraid that if Gerda saw roses she would think of her own, and remember little Kay, and run away.

Then she took Gerda out into the flower garden. What fragrance was there, and what loveliness! Every flower you could think of was there in full bloom; there were those of every season; no picture-book could be gayer and prettier. Gerda jumped for joy, and played till the sun went down behind the tall cherry-trees. Then she was put into a lovely bed with red silk pillows stuffed with blue violets, and she slept there, and dreamt as happily as a queen on her wedding-day.

Next day she could again play with the flowers in the warm sun shine ; and thus many days went by. Gerda knew every flower; but, many as there were, it still seemed to her as if one were missing, but which one she did not know. One day she sat looking at the old woman’s sun-hat with the painted flowers, and it happened that the prettiest of them all was a rose. The old woman had forgotten to remove it from her hat when she made the others sink into the ground. But so it always is when one does not keep one’s wits about one.

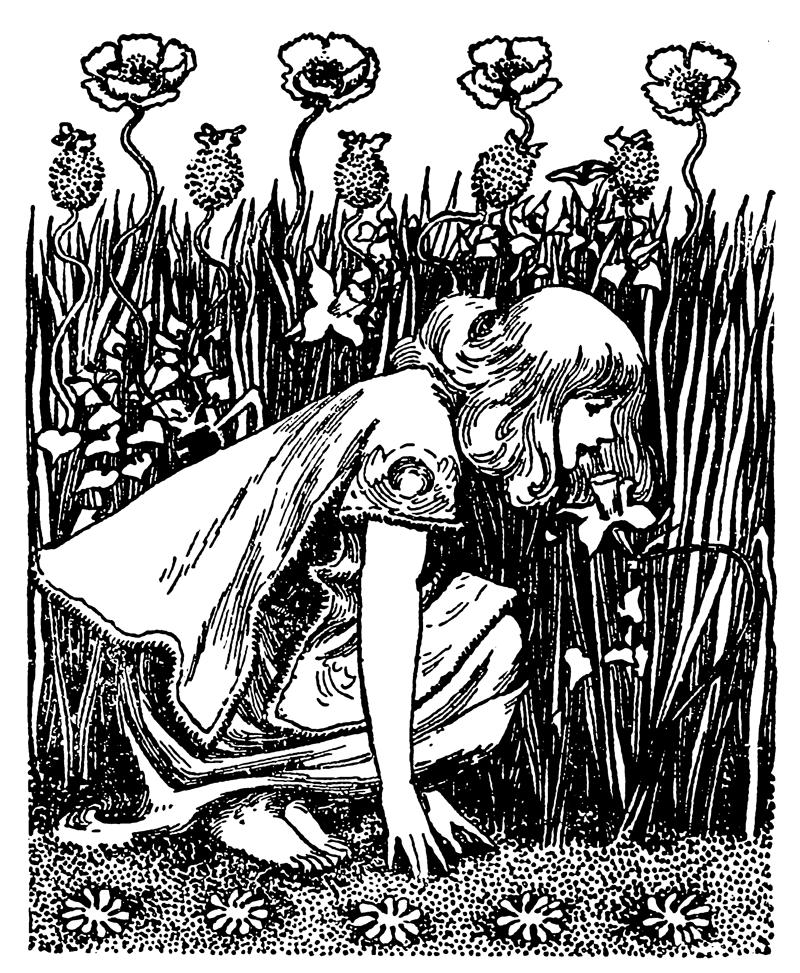

“What, are there no roses here?” cried Gerda.

And she went among the beds, and searched and searched, but there was not one to be found. Then she sat down and cried; and her hot tears fell just upon a spot where a rose-tree lay buried, and when the warm tears moistened the earth the tree at once shot up again as blooming as when it had sunk; and Gerda embraced it, kissed the roses, and thought of the beautiful roses at home, and with them of little Kay too.

“Oh, how I have been wasting my time!” said the little girl, “I who ought to have been looking for little Kay! Do you know where he is?” she asked the roses. “Do you think he is dead?”“He is not dead,” said the roses. “We have been in the ground. All the dead people are there, but Kay is not there.”

“Thank you,” said little Gerda; and she went to the other flowers, looked into their cups, and asked, “Do you not know where little Kay is?”

But every flower stood in the sun thinking only of her own story or fairy-tale. Little Gerda heard many, many of them; but no one knew anything of Kay.

And what said the tiger-lily?

“Do you hear the drum ‘rub-a-dub ’? There are only three notes, always ‘rub-a-dub’! Hear the funeral chant of the women! Hear the call of the priests! The Hindu woman stands in her long red robe on the funeral pile; the flames rise up round her and her dead husband; but the Hindu woman is thinking of the living one here in the circle, of him whose eyes burn hotter than flames, whose glances burn in her soul more ardently than the flames themselves which are soon to burn her body to ashes. Can the flame of the heart die in the flames of the funeral pile?”

“I don’t understand that at all!” said little Gerda.

“That is my story,” said the lily.

What says the convolvulus?

“Over the narrow mountain path hangs an old knight’s castle: the ivy grows thick over the crumbling red walls, leaf by leaf up to the balcony, and there stands a beautiful girl. She leans over the balustrade and gazes up the path. No rose on its stem is fresher than she; no apple blossom wafted by the wind floats more lightly along. How her costly silks rustle! ‘Will he never come?’”

“Is it Kay you mean?” asked little Gerda.

“I am only talking of my own story—my dream,” replied the convolvulus.

What said the little snowdrop?

“Between two trees a board is hanging on ropes: it is a swing. Two pretty little girls, with dresses as white as snow and green silk ribbons on their hats, are sitting on it, swinging. Their brother, who is bigger than they are, stands on the swing with his arm round the rope to hold himself, for in one hand he has a little bowl, and in the other a clay pipe: he is blowing soap-bubbles. The swing moves, and the bubbles fly up with beautiful changing colours; the last one still hangs from the bowl of the pipe, swayed by the wind. The swing goes to and fro. A little black dog, light as the bubbles, stands up on his hind legs and wants to be taken on to the swing. It goes on, and the dog falls, and barks with anger: the bubble bursts. A swinging board and a shimmering foam-picture—that is my song!”

“It may be very pretty, what you’re telling me, but you speak so mournfully, and you don’t mention little Kay at all.”

What do the hyacinths say?

“There were three beautiful sisters, transparent and delicate. The dress of one was red, of the second blue, and of the third pure white. Hand in hand they danced by the calm lake in the bright moonlight.

They were not elves—they were human-born. It was so sweet and fragrant there! The girls disappeared in the forest, and the fragrance became sweeter still. Three coffins, with the three beautiful maidens lying in them, glided from the wood-thicket across the lake; the fireflies flew gleaming round them like little hovering lights. Are the dancing girls sleeping, or are they dead? The flower-scent says they are dead. The evening bell tolls their knell!”

“You make me quite sorrowful,” said little Gerda. “Your scent is so strong, I cannot help thinking of the dead maidens. Ah! is little Kay really dead? The roses have been down beneath the ground, and they say no.”

“Ding, dong!” rang the hyacinth bells. “We are not tolling for little Kay—we do not know him; we only sing our song, the only one we know.”

And Gerda went to the buttercup, shining out among the green leaves.

“You are a little bright sun,” said Gerda. “Tell me, if you know—where shall I find my playfellow?”

And the buttercup shone so gaily, and looked back at Gerda. What song could the buttercup sing? It was not about Kay.

“In a little courtyard God’s bright sun shone warm on the first day of spring. The sunbeams glided down the white wall of the neighbouring house. Close by grew the first yellow flower, shining like gold in the bright sunbeams. An old grandmother sat out of doors in her chair; her pretty granddaughter, a poor maid-servant, had come home for a short visit: she kissed her grandmother. There was gold, heart’s gold, in that blessed kiss, gold on the lips, gold on the ground, gold in the morning hour. See, that is my little story,” said the buttercup.

“My poor old grandmother!” sighed Gerda. “Yes, she is surely longing for me and grieving for me, just as she did for little Kay. But I shall soon go home again and bring Kay with me. There is no use in my asking the flowers: they only know their own song, and give me no information.” And then she tucked her little frock round her, that she might run the faster; but the jonquil struck her on the leg as she jumped over it, and she stopped to look at the tall flower, and asked, “Do you, perhaps, know anything?”

And she bent close down to the flower. And what did it say?

“I can see myself! I can see myself!” said the jonquil. “Oh! oh! how sweet my scent is! Up in the little attic stands a little dancing girl half dressed. She stands sometimes on one foot, sometimes on both; she seems to tread on all the world. She’s nothing but a delusion: she pours water out of a teapot on a bit of stuff—it is her bodice. ‘Cleanliness is a good thing,’ she says. Her white frock hangs on a hook; it has been washed in the teapot too, and dried on the roof.

She puts it on and ties her saffron kerchief round her neck, and the dress looks all the whiter. Point your toes! Look how she seems to stand on a stalk! I can see myself! I can see myself!”

“I don’t care at all about that!” said Gerda. “It is no use your telling me!”

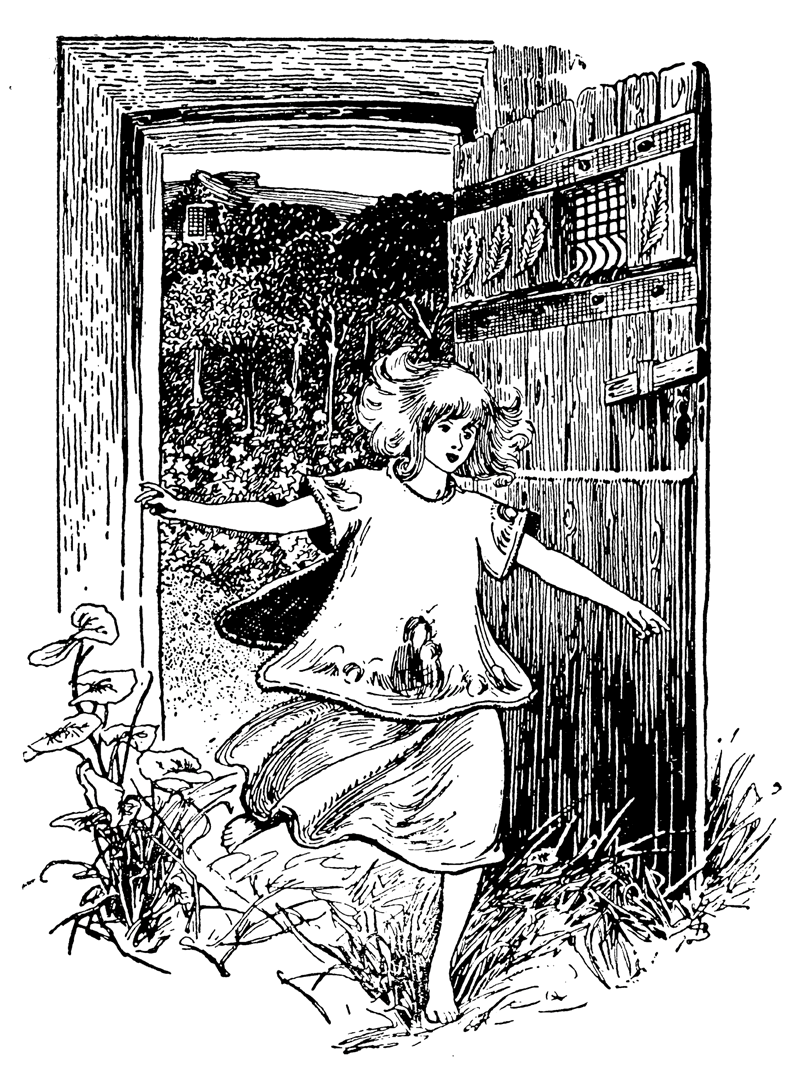

And then she ran to the end of the garden. The door was locked, but she pressed against the rusty latch, and it gave way, the door sprang open, and little Gerda ran with bare feet out into the wide world. She looked back three times, but no one was there to come after her. At last she could run no more, and she sat down on a big stone; and when she looked round she saw that summer was over—it was late in the autumn. No one could know that in the beautiful garden, where there was always sunshine, and where the flowers of every season were always blooming.

“Alas! how I have lost my time!” said little Gerda. “It is already autumn! I must not stay any longer.”

And she got up to go on. Oh, how sore and tired were her little feet! And all around looked so cold and bleak; the long willow leaves were quite yellow, and the mist dripped from the trees like rain; one leaf dropped after another—only the sloe still bore fruit, but the fruit was sour, and set the teeth on edge. Oh, how grey and gloomy it looked out in the wide world!

THE SNOW QUEEN – FOURTH STORY