The History of Rumpelstiltskin

The Legend of Rumpelstiltskin is a tale of primarily European heritage, dating back to at least the sixteenth century.

The Legend of Rumpelstiltskin is a tale of primarily European heritage, dating back to at least the sixteenth century. Many folklorists have studied the legend, the most notable of which has been Edward Clodd, who produced an entire book on Tom-Tit-Tot (the English name of the story) titled An Essay on Savage Philosophy in Folk-Tale (1898). The legend is indeed ‘savage’ in parts, encompassing vice-ridden characters, deceit, maleficent goblins and grizzly endings. It takes the form of Aarne-Thompson type 500: ‘the name of the helper’, as in almost every variant of the narrative, the plot centres around the discovery of the name of a troublesome, though not necessarily evil ‘helper’. This assistant is, of course, the Rumpelstiltskin character.

SELECTED BOOKS

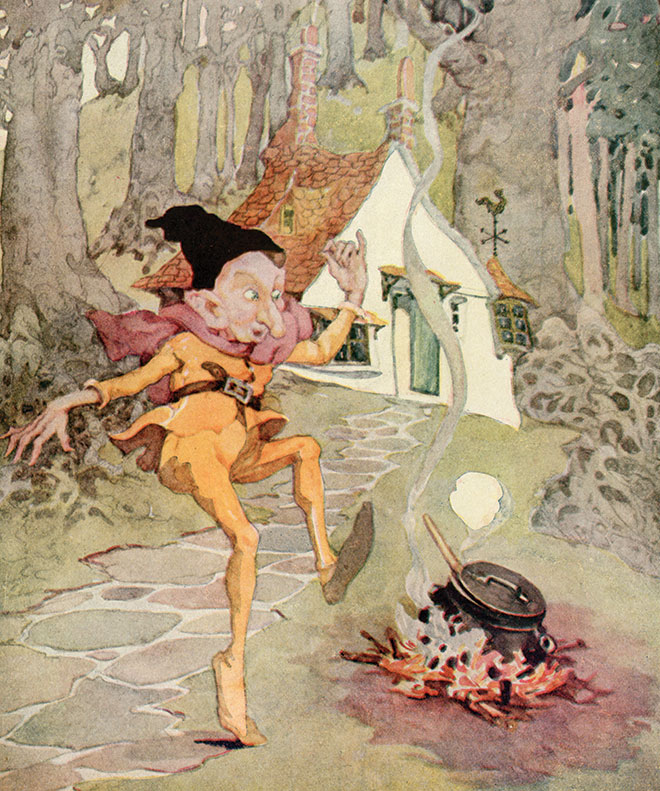

The same story pattern appears in numerous other cultures

The same story pattern appears in numerous other cultures: Whuppity Stoorie in Scotland (from Robert Chambers’ Popular Rhymes of Scotland), Gilitrutt in Iceland, Joaidane in Arabic (‘he who talks too much’), Khlamushka Хламушка (‘junker’) in Russia, and Ruidoquedito (meaning ‘little noise’) in South America. The most famous version of the Rumpelstiltskin narrative was penned by the Brothers Grimm, however, and it was from this tale that most subsequent folklorists took their inspiration. The story was collected in their 1812 edition of the Grimms’ Kinder und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales), and subsequently revised and refashioned in their final 1857 volume. The narrative was so well known across Europe by this point that the Grimms actually collected four versions of the legend – which they combined into the Rumpelstiltskin plot best recognised today.

The most famous Rumpelstiltskin narrative was penned by the Brothers Grimm

To give a brief overview of the story, the Grimm’s adaptation starts with a miller who lies to the King that his daughter can spin straw into gold (recalling the mystical and much-sought-after practice of alchemy). The King demands that the girl perform this act and shuts her in a tower filled with straw and a spinning wheel, threatening to kill her if she is incapable. Naturally, she has given up all hope until an imp-like creature appears in the room and spins the straw into gold for her in return for a necklace. This arrangement continues, in successively larger rooms, until the girl has run out of jewellery. The king, this time, has promised to marry the girl if she completes the task, and so the imp extracts a promise that her firstborn child will be given to him. Time passes, and when her first child is born, the imp returns. The (now-Queen) offers him all her wealth if she may keep the baby. The imp has no interest in her wealth but offers to give up his claim if the Queen can guess his name within three days…

The name ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ is thought to have derived from an old children’s game named Rumpele stilt oder der Poppart, which was mentioned in Johann Fischart’s Geschichtklitterung, or Gargantua (1577). Fischart (1545 – 1591) was a German satirist and publicist, and his game was the 363rd ‘amusement’ in his book. Still played in some parts of Germany, ‘rumpeln’ meant to make a noise, and ‘Stilzer’ referred to someone with a limp. The archaic German word ‘Stülz’ also means ‘lame’ or ‘with a limp’, and so ‘Rumpelstilzchen’ was conceived as a noisy goblin with a limp (directly translating as ‘little rattle stilt’). Children would take turns to assume the role of the marauding goblin (also called a pophart or poppart) that makes noises by rattling pots and rapping on planks. The meaning is also similar to rumpelgeist (‘rattle ghost’) or poltergeist, a mischievous spirit that clatters and moves household objects.

Although this is the first mention of ‘Rumpelstiltskin’, Fischart’s book was actually a loose adaption of an earlier time, that of the Frenchman Francois Rabelais (1483 – 1553). Both these men were skilled satirists and humourists who took great delight in manipulating and inventing words or phrases. Rabelais’s work The Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel (published between 1534 and 1564) told of the adventures of two giants, featuring much crudity, scatological humour and violence. Elements which greatly amused Fischart!

The name ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ is thought to have derived from an old children’s game

This ‘crude’ beginning helps to explain the format of the Rumpelstiltskin narrative as we know it today – there are no beautiful princesses rescued by knights on horseback. Instead, the story revolves around a young woman (often depicted as a lazy and ungrateful daughter), married to a King through dishonest means, and the self-seeking ‘goblin’ character that provides the dubious ‘aid’ (the tale of The Valiant Little Tailor also features a similarly self-seeking protagonist). Names are also of great significance in folklore; the only character who generally has a name is Rumpelstiltskin (Tom Tit Tot in Joseph Jacob’s variant, Whuppity Stoorie for Robert Chambers, Kinkach Martinko in the Slavic tale, or Titteli Ture in the Swedish story, the list goes on…). It is only when the young girl discovers the little man’s name that she gains power over him.

The name ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ could also suggest a darker theme, with ‘little rattle stilt’ taking on a phallic interpretation. The impish creature ‘makes gold’ with the young girl each night and then demands her firstborn (which may very well be his to take). Thus the story could be interpreted in the form of a ‘women’s tale’; a forewarning about what married life could be like for a young, uneducated and easily manipulated female. It is only once the girl knows what to call the visiting imp (thus gaining masculine knowledge), that she is able to control her own fate. In the Mongolian derivation, The Use of Magic Language (the only story to feature a male lead), the Prince is explicitly sent on a quest ‘to gain knowledge’, before he meets his untimely end.

READ RUMPELSTILTSKIN TALES NOW

Such elements also suggest a ‘shadow-animus’ narrative, a coming-of-age tale, where the young protagonist is ‘trapped’ until they are able to grow into maturity by rebelling against their elders. The young girl (as the character is most often portrayed) has, after all, been betrayed three times by those in a position of trust; her parent, her husband, and the Rumpelstiltskin character. Three is a highly significant number as well, representative of the Holy Trinity; there are three fairies in Giambattista Basile’s Italian variant, three nights of spinning, and three ‘gifts’ that the young woman must give to Rumpelstiltskin in the Grimms’ tale (the necklace, the ring and the first-born child); three guesses allowed by Tom Tit Tot (the English variant) and again, three days of captivity in the Slavic tale of Kinkach Martinko.

As well as altering the name of the antagonist, the differing versions from Europe and the wider world present the basic narrative in strikingly imaginative ways. Giambattista Basile, a Neapolitan poet and courtier, published the first full-length printed version of the Rumpelstiltskin-type narrative in his Pentamerone (1634 – 36). Whilst differing substantially from the Grimms‘ later tale, Basile did introduce the main features of the narrative; the lie about the young girl’s ability to spin flax, her subsequent marriage to a wealthy (though demanding) husband, and the ‘aid’ of the helper (this time fairies, instead of the imp). Crucially though, Basile’s story is the only version not to have a name-guessing game.

The Swedish version presents the Rumpelstiltskin character (named Titteli Ture) as an ugly and deformed man, described later in the tale as a dwarf. This change is significant and arguably a mistranslation, as in the original German, the Grimms referred to Rumpelstiltskin as a ‘männlein’ (little man) as opposed to the word ‘Zwerge’, meaning dwarf. In traditional fairy-tale narratives, dwarves are largely irrelevant beings with little or no magical powers. In contrast, Männlein’s are more associated with goodness; for example, in the Grimm’s The Three Männlein of the Woods, the wise and knowledgeable creatures help the young girl to marry the prince.

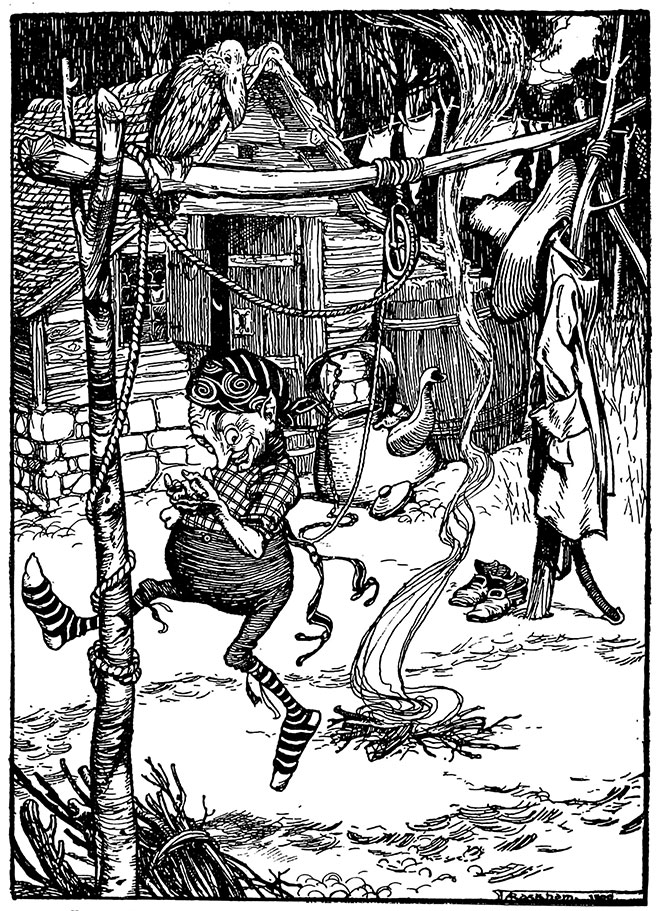

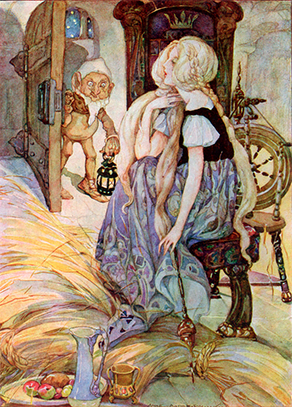

‘Suddenly the door opened, and in stepped a tiny little man. ‘ Illustration by H. J. Ford

Rumpelstiltskin, Anne Anderson 1919

Indeed, although he doesn’t seem good, Rumpelstiltskin is incredibly knowledgeable, being able to spin the gold that the young woman requires. Spinning itself has obvious connotations with fate (the three fates) as the activity which is used to control people’s destinies. If Rumpelstiltskin is thus as wise and as powerful as the imagery would suggest, why does he then give the young woman a chance to escape her fateful promise and keep her firstborn? Rumpelstiltskin could be portrayed as a devil-like character, trying to tempt the woman into the sin of giving up her child. But by offering the woman a chance at ‘redemption’, his behaviour hints at the double-sided temperament of männlein’s, fairies, imps and the like, with both good and bad elements to their character.

At the end of the Grimms’ tale (though not in any others), Rumpelstiltskin symbolically rips himself in two, thus revealing his dual nature. There are no overt morals to the story; it could be read as a warning against making promises that can’t be fulfilled, a warning against bragging, idleness or lies, or even a cautionary tale that transforms (turning straw into gold and the girl into a queen), does not come without a price. But, as in all great tales, the exact interpretation is left up to the reader.

As a testament to this story’s ability to inspire and entertain generations of readers, Rumpelstiltskin continues to influence popular culture internationally, lending plot elements, allusions and tropes to a wide variety of artistic mediums. The tale has been translated into almost every language across the globe and, very excitingly, is continuing to evolve in the present day.

More on Rumpelstiltskin

Selected Books