Rumpelstiltskin – And Other Angry Imps with Rather Unusual Names

This book is part of our beloved Origins of Fairy Tales from Around the World Series which showcases the amazing breadth and diversity involved in folkloric storytelling. It focuses on the phenomenon that the same tales, with only minor variations, appear again and again in different cultures – across time and geographical space. The tales included in these collections are enhanced by the addition of stunning illustrations by talented artists from the Golden Age of Illustration.Rumpelstiltskin – And Other Angry Imps with Rather Unusual Names

Rumpelstiltskin is a tale of primarily European heritage, dating back to at least the sixteenth century. The story has been studied by many folklorists, the most notable of which has been Edward Clodd, who produced an entire book on Tom-Tit-Tot (the English name of the story) titled An Essay on Savage Philosophy in Folk-Tale (1898). The legend is indeed ‘savage’ in parts, encompassing vice-ridden characters, deceit, maleficent goblins and grizzly endings.

The most famous version of the Rumpelstiltskin narrative was penned by the Brothers Grimm however, and it was from this tale that most subsequent folklorists took their inspiration.”

The stories within:

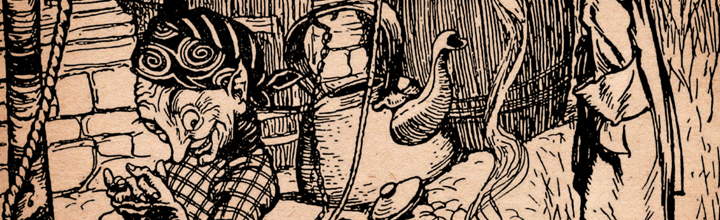

‘The little man dashed his right foot so deep into the floor that he was forced to lay hold of it with both hands to pull it out.’ Illustration by Kay Nielsen

The Seven Bits of Bacon Rind (An Italian Tale)

The Seven Bits of Bacon Rind was written by Giambattista Basile (1566-1632). It was first published in his collection of Neapolitan fairy tales titled Lo Cunto de li Cunti Overo lo Ttrattenemiento de Peccerille in 1634.

Many of the fairy tales that Basile collected are the oldest known variants in existence, including this, the first full-length printed version of a Rumpelstiltskin-type narrative. The story differs substantially from the Grimm’s better-known version, though it also introduces several key tropes: the lie about the young girl’s ability to spin flax, her subsequent marriage to a wealthy husband, the ‘aid’ of the helper (this time some fairies). Unlike Rumpelstiltskin, Basile’s fairies ask for nothing in return for their help, and likewise, do not suggest the name-guessing game.

Rumpelstiltskin (A German Tale)

Rumpelstiltskin, collected by the Brothers Grimm, was first published in Kinder und Hausmärchen (‘Children’s and Household Tales’) in 1812.

Unlike the Italian version of the tale, the woman in the Grimm’s narrative is portrayed as a beautiful young woman. Her ability to spin straw is likewise exaggerated – but this time, she is said to be able to ‘spin straw into Gold.’ In the Grimm’s, slightly darker narrative, she is asked to trade all her worldly possessions until she has nothing left. In a similar manner to Basile’s tale, as a result of this artifice, the girl is subsequently married to the King. She manages to escape the promise she has made to the ‘helper’.

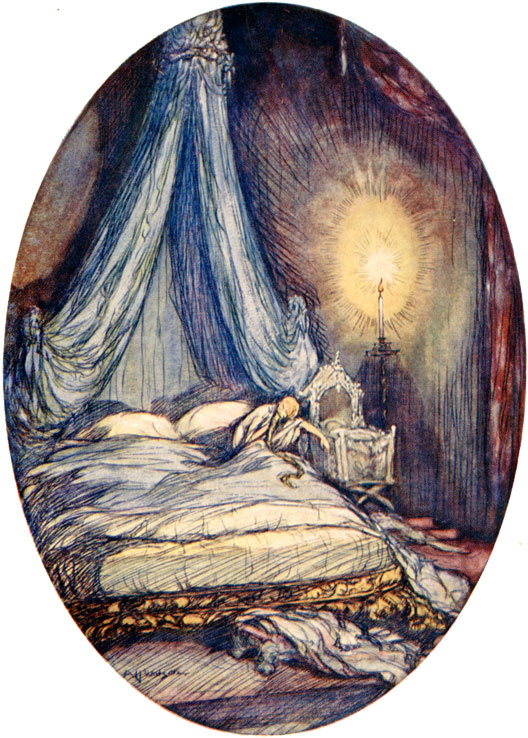

‘All that night the Queen lay wide awake, a glimmering light beside her bed.’ Illustration by A. H. Watson

The Girl Who Could Spin Gold from Clay and Long Straw (A Swedish Tale)

The Girl Who Could Spin Gold from Clay and Long Straw is a story collected by Benjamin Thorpe (1782 – 1870) and published in Yule-Tide Stories: A Collection of Scandinavian and North German Popular Tales and Traditions (1853).

In this version of the Rumpelstiltskin narrative, the young woman (who is good and amiable, though also indolent) is visited not by an imp-like creature, but by an old man. Instead of weaving the straw himself, he gives her a magical pair of gloves, with which she will be able to complete the task. If she cannot guess his name she will have to be his bride.

Whuppity Stoorie (A Scottish Tale)

Whuppity Stoorie is a Scottish fairy tale collected by Robert Chambers (1802 – 1871) in his Popular Rhymes of Scotland (published in 1858).

The story is traditionally classed as a Rumpelstiltskin narrative, although guessing the name of a helper to rescue a baby is the only main commonality. Akin to Basile’s version, the ‘helper’ is not an imp-like creature, but a fairy. In a similar manner to the Grimm’s tale, the fairy demands the first-born child in return for her help – which can only be prevented by guessing her name.

The Use of Magic Language (A Mongolian Tale)

The Use of Magic Language is a tale written down by Rachel Harriette Busk (1831 – 1907) in Sagas from the Far East, or Kalmouk and Mongolian Traditional Tales (1873).

Although most of the details of the Rumpelstiltskin narrative are different (unsurprisingly so for such a geographical reach), the basic element of the story has stayed the same. Here, a young prince is sent on a journey in order to gain all sorts of knowledge, taking with him a companion. On their return, the companion, being jealous of the Prince’s superior knowledge, kills him. As the prince dies, he utters the word, ‘Abaraschika.’ When the murderer reaches the palace, he tells the sorrowing King how the prince fell sick unto death, and that he had time to speak only the above word. Consequently, the King sends out his servants to find the meaning of the word.

Tom Tit Tot (An English Tale)

Tom Tit Tot is an English fairy tale collected by Joseph Jacobs (1854 – 1916) in his English Fairy Tales (published in 1890).

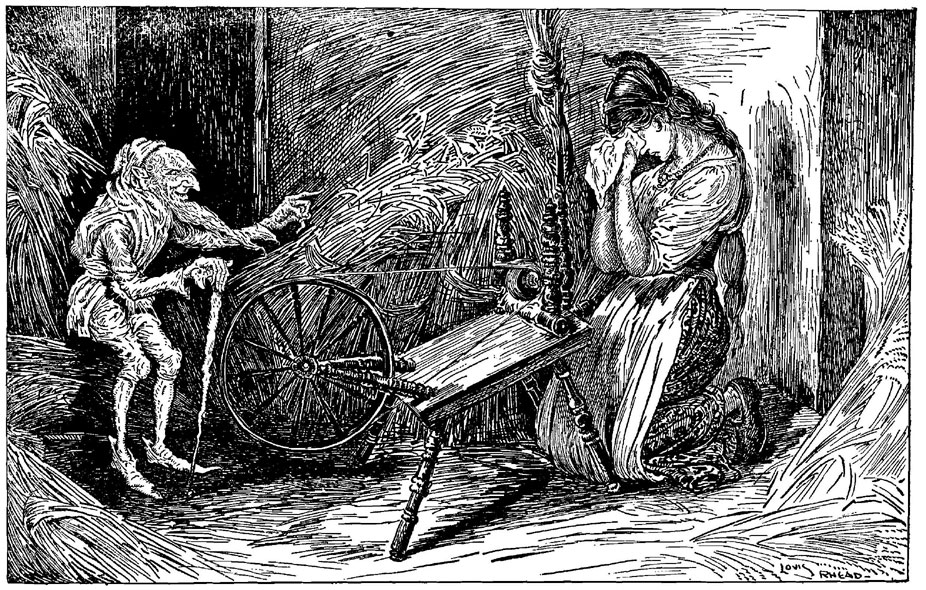

Jacob’s version is very similar to the Grimm’s and Giambattista Basile’s stories. Like the Italian narrative, the young woman is portrayed as lazy and greedy. But like the German tale, the name-guessing game is crucial to the story. Instead of the young woman’s first born being offered up as the prize, it is the woman herself in Jacobs version. The imp is also a lot scarier, with black outstretched hands, and a whirling tale – and the girl must spin flax for an entire month. In a unique departure, however, it is the King that discovers the imp’s name, unknowingly passing this information onto his new wife.

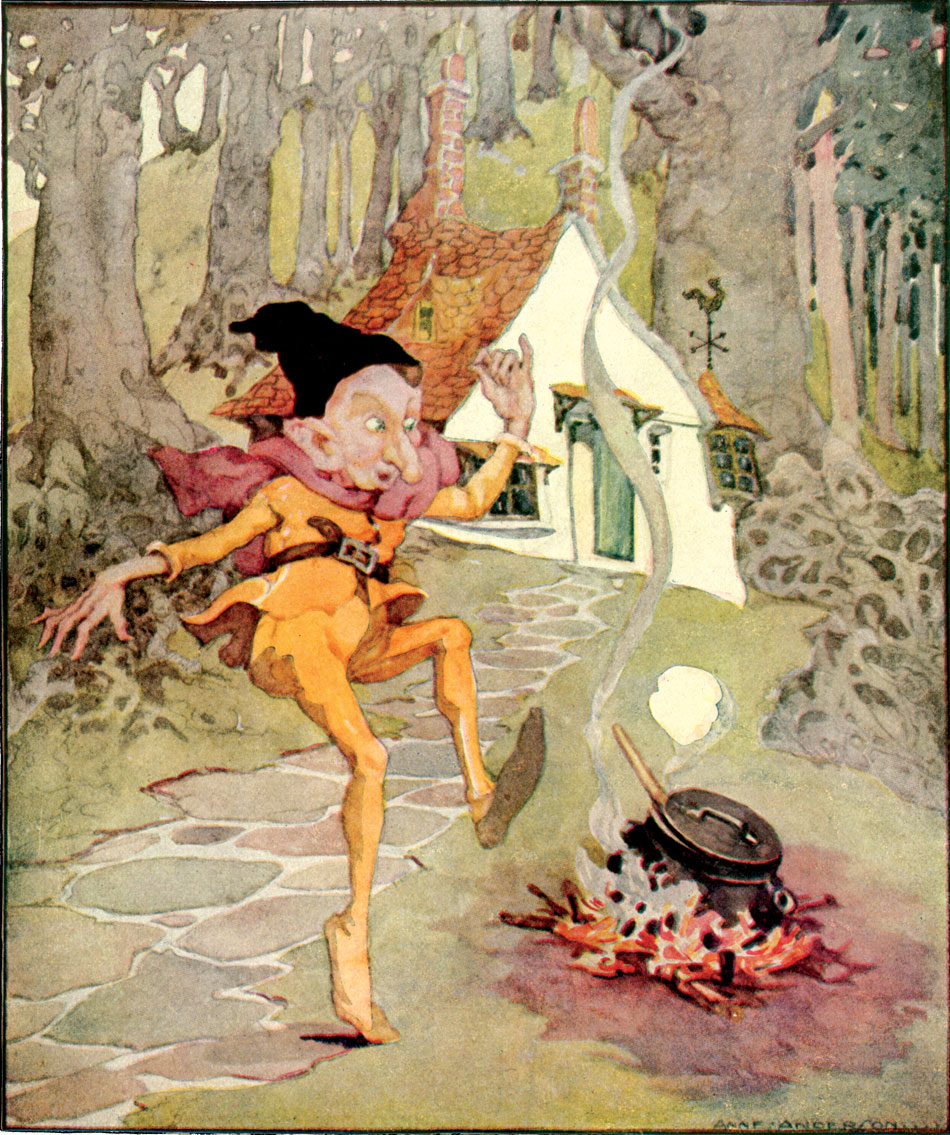

“Today I brew, tomorrow I bake. The next day the Queen’s child I take.” Illustration by Anne Anderson

Kinkach Martinko (A Slavic Tale)

Kinkach Martinko was written down by Aleksander Borejko Chodźko, a Polish poet, Slavist and Iranologist. It appeared in Fairy Tales of the Slav Peasants and Herdsmen (translated by Emily J. Harding in 1896).

This tale (although with an unusually violent opening), progresses in a similar manner to most ‘name of the helper’ narratives. Like the Swedish variant, the maleficent character is portrayed as a small man, but one who asks the young woman to guess the material his boots are made of – as well as telling him his proper name. Unusually for this story-type, a third main character is introduced; another old man, who because of the young girl’s kindness, tells her the name of the ‘helper.’

We hope you’ve enjoyed reading about this classic fairy tale and it’s many variations from around the world.

We hope you’ve enjoyed reading about this classic fairy tale and it’s many variations from around the world.

If you would like to purchase this book to read these tales in full click here.

If you would like to read more about Rumpelstiltskin visit our page on the History of Rumpelstiltskin.