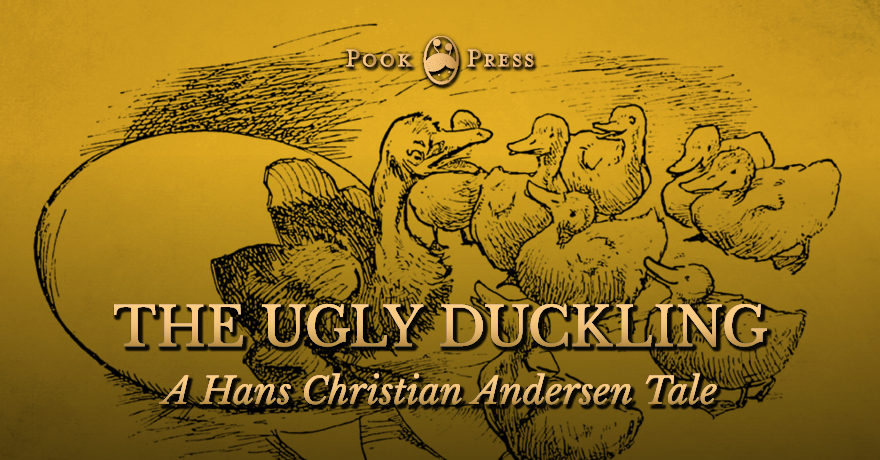

The Ugly Duckling by Hans Christian Andersen

Written by the Danish Hans Christian Andersen, The Ugly Duckling was published for the first time in 1843 and has been printed in fairy tale collections ever since. The book can be seen as a metaphor for the hardships faced during the stages of growth when going from being a child to being an adolescent. It shows us that one must be accepting of ones differences, even if one doesn’t fit in with a group.

In the tale, a swan is born to a family of ducks and goes from place to place being despised and judged by all whom he meets. In the end he transforms into a swan and finds his true place in the world.

‘….he was so happy, and yet not at all proud, for a good heart is never proud’

The Ugly Duckling

By Hans Christian Andersen

It was delightful out in the country: it was summer, and the corn fields were golden, the oats were green, the hay had been put up in stacks in the green meadows, and the stork went about on his long red legs and chattered Egyptian, for this was the language he had learned from his mother. Round the fields and meadows were great forests, and in the midst of the forests lay deep lakes. Yes, it was really delightful out in the country! In the midst of the sunshine there lay an old manor-house, with deep canals round it, and from the wall down to the water grew large burdocks, so high that little children could stand upright under the tallest of them. It was just as wild there as in the deepest wood. Here sat a duck upon her nest, for she had to hatch her ducklings, but she was almost tired out, for it took such a long time; and she so seldom had visitors. The other ducks liked better to swim about in the canals than to climb up to sit under a burdock and cackle with her.

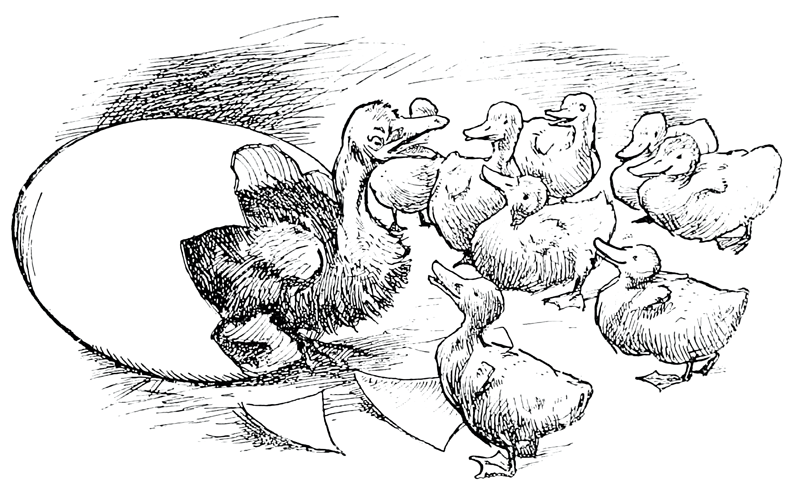

At last one egg after another cracked open. “Piep! piep!” they cried; all the yolks had come to life, and little heads were peeping out.

“Quack! quack!” said the duck, and they all came out quacking as fast as they could, looking all round them under the green leaves, and the mother let them look as much as they wished, for green is good for the eyes.

“How wide the world is!” said the young ones, for they truly had much more room now than when they were in the eggs.

“Do you think this is the whole world?” said the mother. “That stretches far across the other side of the garden, quite into the parson’s field; but I have never been there yet! I hope you are all here,” she said, and she stood up. “No, I haven’t got you all. The biggest egg is still there. How long is this going to last? I am getting tired of it.” And she sat down again.

“Well, how goes it?” said an old duck, who had come to pay her a visit.

“It’s taking so long with that one egg,” said the duck sitting there.

“It will not break. But look at the others! They are the prettiest ducklings I have ever seen! They are all just like their father, the rascal! He never comes to see me.”

“Let me see the egg which will not break,” said the old one. “Depend upon it, it is a turkey’s egg! I was once cheated in that way, and had a lot of bother and trouble with the young ones, for they are afraid of the water. I could not get them into it. I quacked and pecked, but it was no use! Let me see the egg. Yes, that’s a turkey’s egg! Let it alone, and teach the other children to swim.”

“I think I’ll just sit on it a little longer,” said the duck. “I’ve sat so long now that I may as well sit a few days more.”

“As you please,” said the old duck, and she went away.

At last the big egg broke. “Piep! piep!” said the little one, and crept out. It was very big and ugly. The duck looked at it.

“That’s a terribly big duckling!” said she; “none of the others look like that: can it really be a turkey-chick? Well, we shall soon find that out! Into the water he shall go, even if I have to push him in myself!”

Next day the weather was splendidly bright, and the sun shone on all the green burdocks. The mother-duck went down to the canal, with all her little ones. Splash!—she sprang into the water. “Quack! quack!” she said, and one duckling after another plumped in. The water closed over their heads, but they came straight up again and swam capitally; their legs went of themselves, and there they were, all in the water, and the ugly grey duckling swimming with them.

“No, he’s not a turkey,” said she; “see how well he uses his legs, and how upright he holds himself! He’s my own child! On the whole he’s quite pretty, if only you look at him properly. Quack! quack! come along with me, and I’ll lead you out into the world, and present you in the poultry-yard; but keep close to me, so that no one may tread on you, and take care of the cats!”

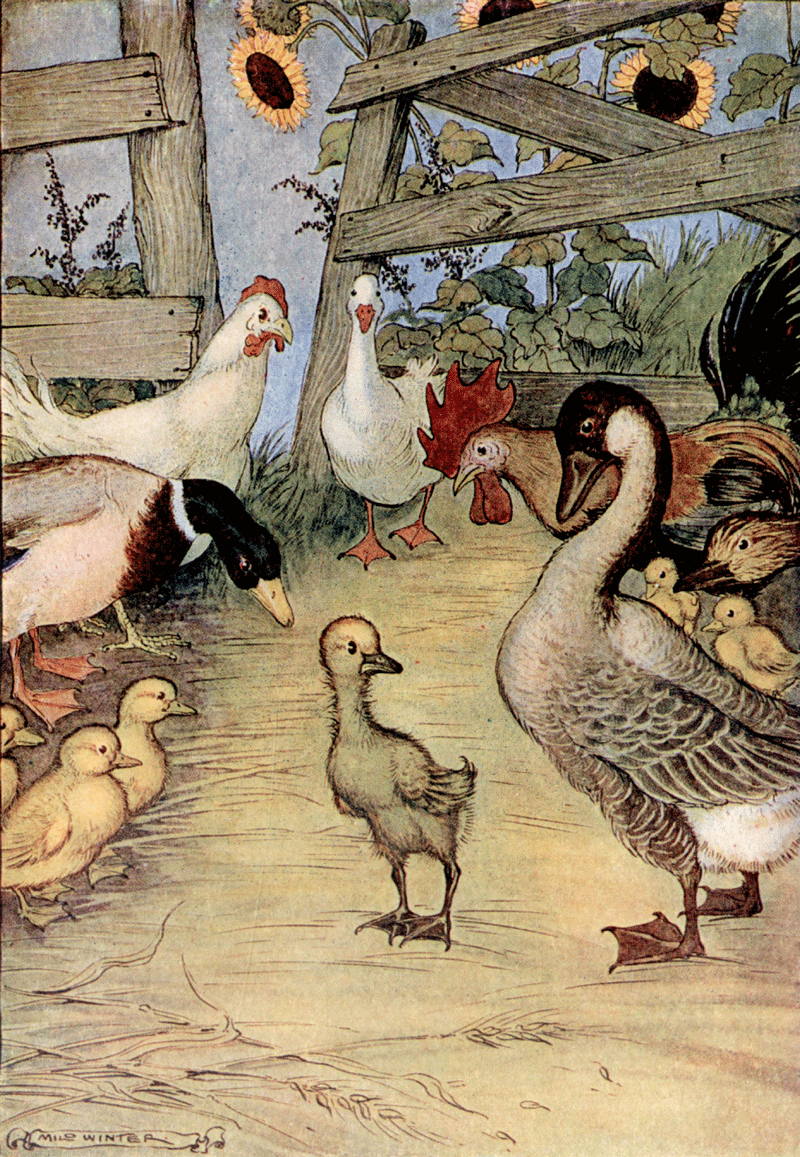

And so they came into the poultry-yard. There was a terrible riot going on there, for two families were quarrelling about an eel’s head, and the cat got it after all.

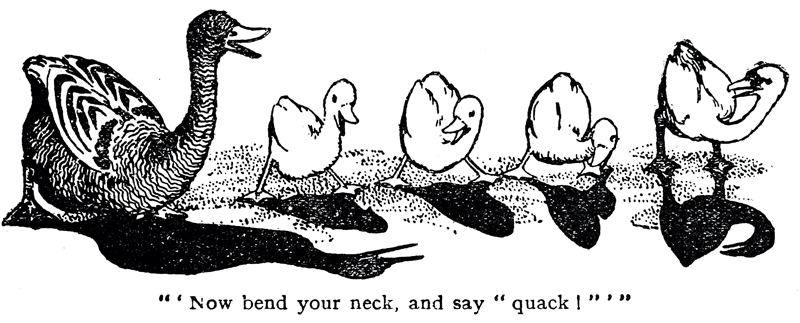

“See, that’s the way of the world!” said the mother-duck; and she whetted her beak, for she too wanted the eel’s head. “Only use your legs,” said she. “See that you bustle about, and bow your heads before the old duck yonder. She’s the grandest of all of them here; she’s of Spanish blood—that’s why she’s so fat, and, do you see, she has a red rag round her leg; that’s something unusually fine, and the greatest distinction any duck can enjoy: it means that they don’t want to lose her, and that she’s to be recognized by man and beast. Stir yourselves—don’t turn in your toes! A well-brought-up duck turns its toes right out, just like his father and mother—so! Now bend your necks and say ‘Quack!’”

And so they did; but the other ducks round about looked at them, and said out loud:

“Look there! Now we’re to have that lot too, as if there were not enough of us already! And—fie!—look how ugly that duckling is! We won’t stand that!” And one duck flew straight at him, and bit him in the neck.

“Let him alone,” said the mother; “he is doing no harm to anyone”.

“Yes, but he’s too big and so different,” said the duck who had bitten him, “and therefore he must be pecked.”

“Those are pretty children that mother has there!” said the old duck with the rag on her leg. “They’re all pretty but that one; that’s not a lucky one! I wish she could hatch him over again!”

“That cannot be, your Highness,” said the duckling’s mother. “He is not pretty, but he has a really good disposition, and swims as well as any other—yes, I may even say better! I think he will grow pretty, and may become smaller in time! He has lain too long in the egg, and therefore has not got the proper shape.” And she stroked his neck and smoothed his feathers. “Moreover, he is a drake,” said she, “and so it does not matter so much. I think he will be very strong, and make his way in the world!”

“The other ducklings are graceful enough,” said the old duck. “Make yourself at home; and if you find an eel’s head you may bring it me.”

So now they felt at home. But the poor duckling which had crept last out of the egg, and looked so ugly, was bitten and pushed and made a fool of, as much by the ducks as by the chickens.

“He is too big!” they all said. And the turkey-cock, who had been born with spurs, and therefore thought himself an emperor, puffed himself up like a ship in full sail, and bore down upon him, and gobbled, and grew quite red in the face. The poor duckling did not know where to stand or where to go; he was quite miserable because he looked ugly, and was the butt of the whole yard.

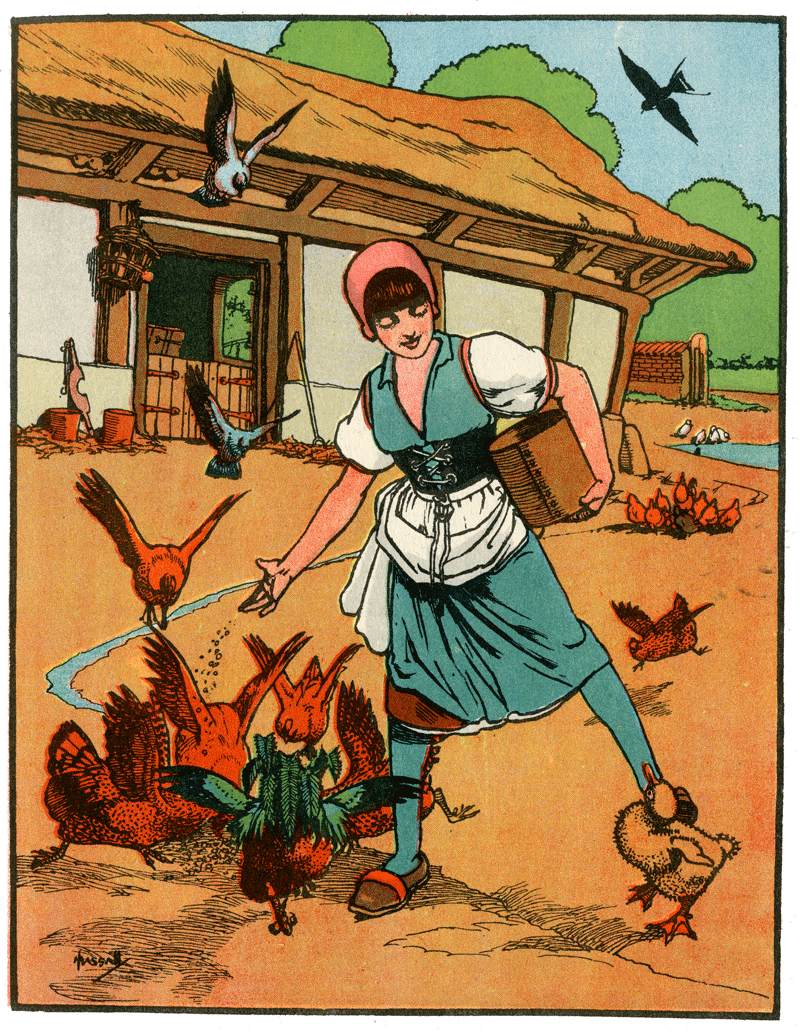

So it went on the first day, and afterwards it became worse and worse. The poor duckling was hunted about by them all; even his brothers and sisters were quite cross with him, and said, “If only the cat would catch you, you ugly sight!” And his mother said, “If you were only far away!” And the ducks bit him, and the chickens pecked at him, and the girl who fed the poultry kicked at him with her foot.

Then he ran and flew over the hedge, and the little birds in the bushes flew up in fear.

“That is because I am so ugly!” thought the duckling; and he shut his eyes, but ran on farther; so he came out into the great moor, where the wild ducks lived. Here he lay the whole night long; he was so tired and sorrowful.

Towards morning the wild ducks flew up, and looked at their new comrade.

“What sort of a one are you?” they asked; and the duckling turned in every direction, and bowed to them as best he could. “You are remarkably ugly!” said the wild ducks. “But that’s all the same to us, so long as you do not marry into our family!”

Poor thing! He certainly was not thinking of marrying, and only hoped to get leave to lie among the reeds and drink some of the marsh water.

Thus he lay two whole days, and then there came two wild geese, or, rather, ganders, for both were males. It was not long since each came out of the egg, and that’s why they were so saucy.

“Listen, comrade” said one them. “You’re so ugly that I like you. Will you go with us, and become a bird of passage? Near here, in another moor, there are a few sweet lovely wild geese, all unmarried, and all able to say ‘Quack!’ You’ve a chance making your fortune, ugly as you are!”

“Bang! bang!” sounded in the air above, and the two ganders fell dead in the swamp, and the water became blood-red. “Bang! bang!” it sounded again, and whole flocks of wild geese rose up from the reeds. And then there was another shot. A great hunt was going on. The hunters were lying in wait all round the moor—yes, some were even sitting up in the branches of the trees, which stretched far over the reeds. The blue smoke rose up like clouds among the dark trees and drifted far over the water; into the mud came the hunting dogs—splash, splash!—and the rushes and the reeds bent on every side. That was a fright for the poor duckling! He turned his head to put it under his wing, but at that moment a frightful great dog stopped close to the duckling. His tongue hung far out of his mouth and his eyes gleamed horribly; he thrust out his nose close to the duckling, showed his sharp teeth, and—splash, splash!—on he went, without touching him.

“Oh, thank heaven!” sighed the duckling. “I am so ugly that even the dog does not want to bite me!”

And so he lay quite still, while the shots rattled through the reeds, and gun after gun went off. At last, late in the day, all was quiet again; but the poor duckling did not dare to move; he waited several hours before he looked round him, and then made off out of the marsh as fast as he could. He ran on over field and meadow, and such a storm was blowing that it was difficult to get along at all.

Towards evening the duckling came to a miserable little peasant’s hut. It was so tumbledown that it did not know which side to fall, and that’s why it remained standing. The storm whistled so fiercely about the duckling that he was obliged to sit down to withstand it; and the tempest grew worse and worse. Then the duckling noticed that one of the hinges of the door had given way, and the door hung so askew that he could slip through the crack into die room; and so he did.

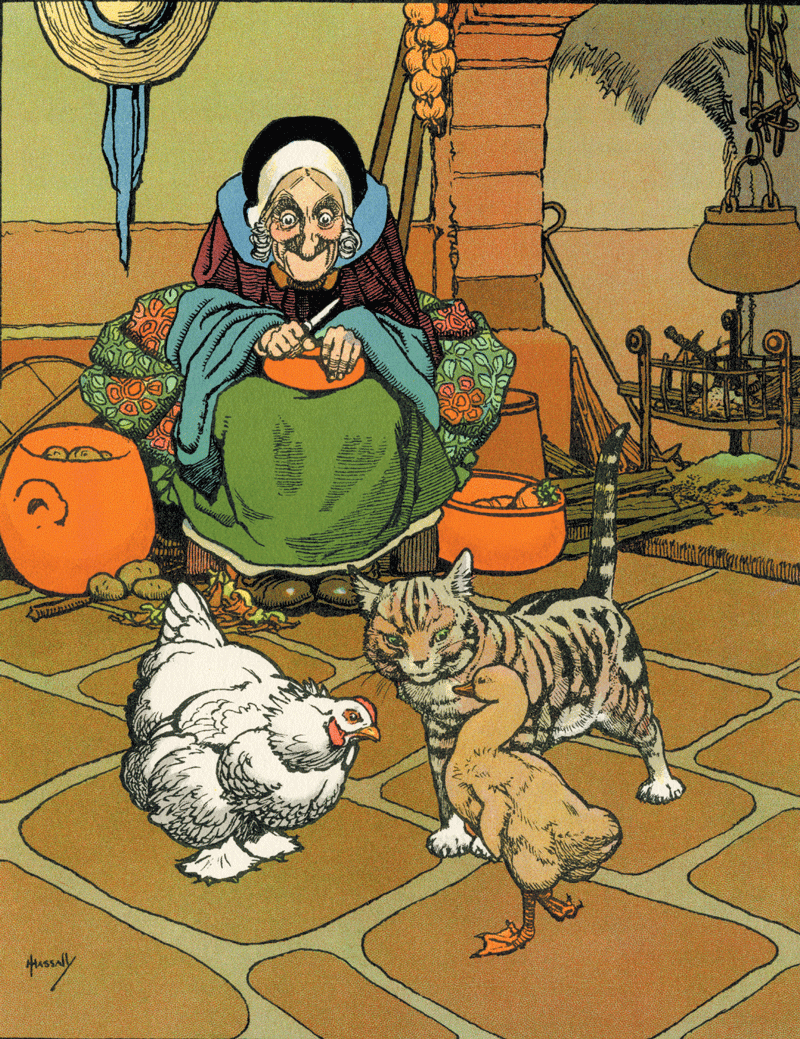

Here there lived a woman, with her tom cat and her hen.

And the tom cat, whom she called Sonnie, could arch his back and purr, and he could even give out sparks, but for that one had to stroke his fur the wrong way. The hen had very little short legs, and therefore she was called Chickabiddy-shortlegs; she laid good eggs, and the woman loved her as her own child.

In the morning the strange duckling was noticed at once, and the tom cat began to purr, and the hen to cluck.

“What’s all this?” said the woman, and looked about her; but she could not see well, and so she thought the duckling was a fat duck that had strayed in. “This is a rare catch!” she said. “Now I shall have duck’s eggs. I hope it is not a drake. That we must find out!”

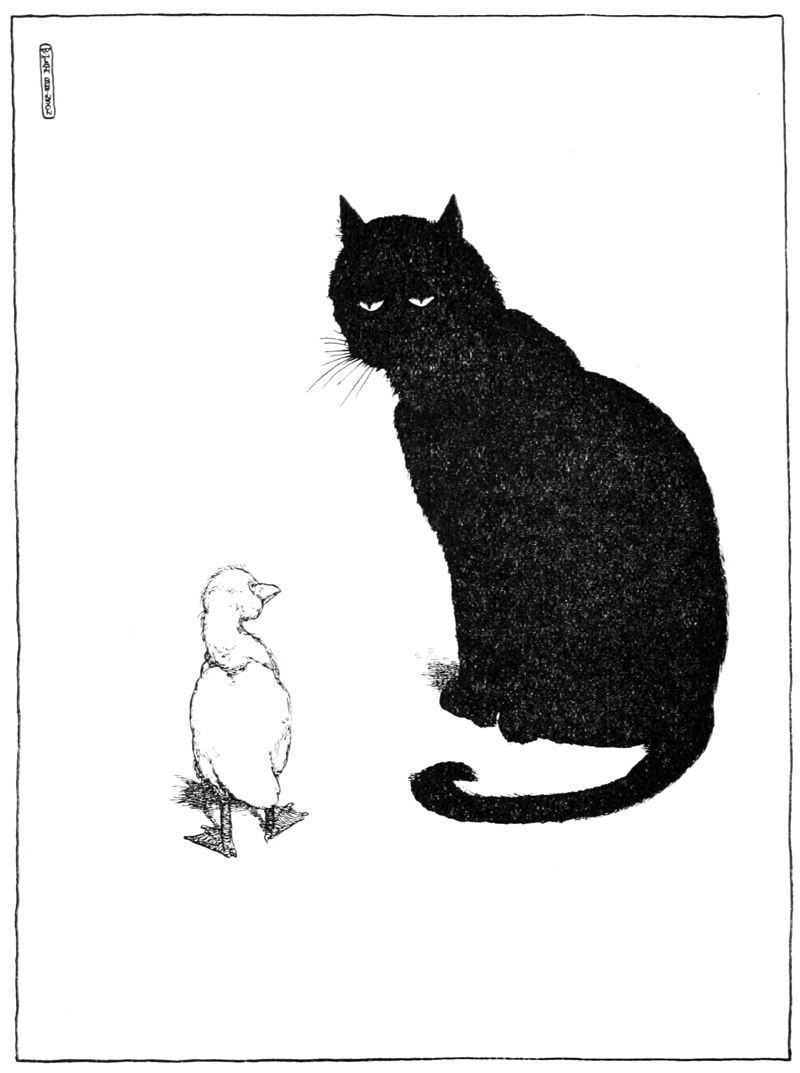

And so the duckling was taken on trial for three weeks; but no eggs came. And the tom cat was master of the house, and the hen was mistress, and always said, “We and the world!” for she thought they were half the world, and by far the better half too. The duckling thought it might be possible to hold another opinion, but the hen would not allow it.

“Can you lay eggs?” she asked.

“No.”

“Then you’d better hold your tongue.”

And the tom cat said, “Can you arch your back, and purr, and give out sparks?”

“No.”

“Then you mustn’t have any opinion of your own when sensible folk are talking.”

And the duckling sat in a corner and was in a sad humour; then the fresh air and the sunshine streamed in; and he was seized with such a strange longing to swim on the water that he could not help telling it to the hen.

“What are you thinking of?” cried the hen. “You have nothing to do, that’s why you have these fancies. Lay eggs or purr and they will pass away.”

“But it is so delightful to swim on the water!” said the duckling, “so delightful to let it close over your head, and dive down to the bottom!”

“Yes, that must be a great pleasure truly,” said the hen. “You must be going crazy. Ask the cat about it—he’s the wisest creature I know—ask him if he likes to swim on the water or to dive under it: I won’t speak of myself. Ask our mistress, the old woman; no one in the world is wiser than she. Do you think she has any longing to swim, and to let the water close over her head?”

“You don’t understand me,” said the duckling.

“We don’t understand you? Then pray who will understand you? You surely don’t pretend to be wiser than the tom cat and the old woman—to say nothing of myself. Don’t be conceited, child, and be grateful for all the kindness that has been shown you. Have you not come into a warm room, and into company where you may learn something? But you are an idle chatterer, and it’s no pleasure to be with you. You may believe me, I speak for your own good. I say unpleasant things to you, and that’s the way you may always know your true friends! Just you learn to lay eggs, or to purr and give out sparks!”

“I think I’ll go out into the wide world,” said the duckling.

“Yes, do, by all means,” said the hen.

And away went the duckling. He swam on the water and dived, but he was slighted by all the other creatures because of his ugliness.

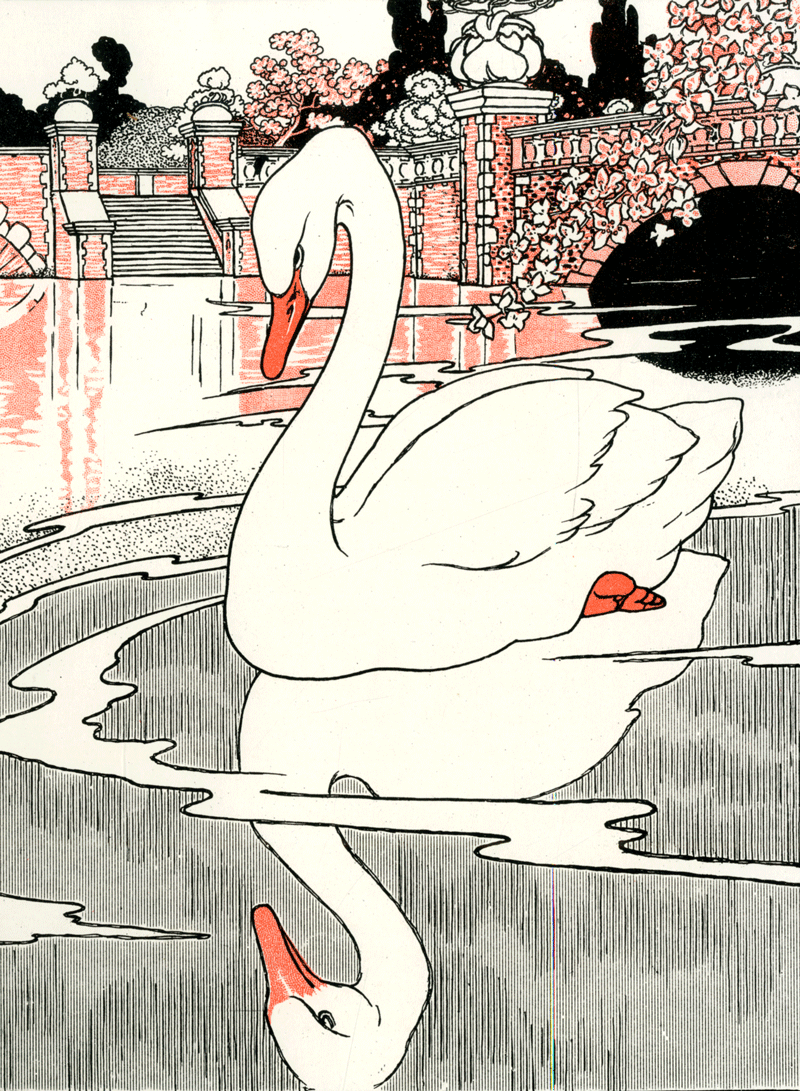

Then autumn came. The leaves in the forest turned yellow and brown, the wind caught them so that they danced about, and the air turned very cold. The clouds hung low, heavy with hail and snow, and on the fence stood the raven and croaked, “Caw! caw!” from sheer cold; yes, it makes one shiver only to think of it. The poor duckling certainly had not a good time. One evening—the sun was just setting in all its beauty—there came a whole flock of great handsome birds out of the bushes. The duckling had never seen anything so beautiful. They were dazzlingly white, with long, slender necks. They were swans; they uttered a very peculiar cry, spread their lovely long wings, and flew away from that cold region to warmer lands, to open lakes. They rose so high, so high, that the ugly little duckling felt quite queer as he watched them. He turned round and round in the water like a wheel, stretched out his neck towards them, and uttered such a strange loud cry that he frightened even himself. Oh! he could not forget those beautiful, those happy birds; and as soon as he could see them no longer he dived right down to the bottom, and when he came up again he was quite beside himself. He knew not what birds they were, nor whither they were flying; but he loved them more than he had ever loved anyone before. He was not at all envious of them. How could he think of wishing for such loveliness as they had? He would have been quite happy if only the ducks would have allowed him to be with them—the poor ugly little thing!

And the winter grew so cold, so cold! The duckling was forced to swim about in the water to prevent it from freezing all over; but every night the hole in which he swam became smaller and smaller. It froze so hard that the icy covering creaked; and the duckling had to use his legs all the time to keep the hole from freezing up. At last he became exhausted, and lay quite still, and soon froze fast into the ice.

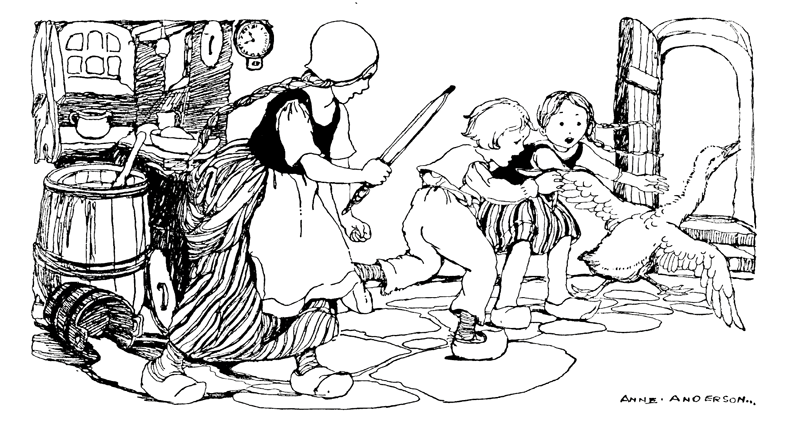

Early in the morning a peasant came by and saw him. And he went on to the ice, and took his wooden shoe and broke the ice to pieces, and carried the duckling home to his wife. There he came to again. The children wanted to play with him, but the duckling thought they would hurt him, and in his fright he fluttered up into the milk-pan, so that the milk splashed all over the room. The woman cried out and clapped her hands, at which the duckling flew into the butter-tub, and then into the meal-barrel and out again. What a sight he was then! The woman screamed, and struck at him with the fire-tongs; the children tumbled over one another in trying to catch the duckling; and they laughed and they screamed! Luckily the door stood open, and the poor creature was able to slip out among the shrubs into the newly fallen snow.

But it would be too sad to tell you all the misery and trouble the duckling had to bear through the hard winter. He was lying out on the moor among the reeds, when the sun began to shine warmly again. The larks were singing, and it was lovely springtime.

Then all at once the duckling flapped his wings: they beat the air more strongly than before, and bore him quickly away; and before he knew it he found himself in a large garden, where the apple-trees were in bloom, and lilacs scented the air and hung their long green branches down to the winding canals. Oh, here it was so beautiful, in the freshness of spring! and right in front of him from thicket came three lovely white swans; they ruffled their feathers, and swam lightly over the water. The duckling knew the splendid creatures, and was seized with a strange sadness.

“I will fly to them, the royal birds! and they will kill me, because I, that am so ugly, dare to go near them. But that will not matter! Better be killed by them than snapped at by ducks, pecked by fowls, and kicked by the girl who takes care of the poultry-yard, and suffer hunger in winter!” And it flew into the water, and swam towards the beautiful swans; they saw him, and came sailing up with ruffled feathers.

“Only kill me!” said the poor creature, and bent his head down to the water and awaited his death. But what did he see in the clear water? He saw below him his own image, but he was no longer a clumsy, dark grey bird, ugly and ungainly; he was himself a swan.

It matters little to be born in a duck-yard when one comes from a swan’s egg!

He felt quite glad at all the trouble and misfortune he had suffered, now he realized his good fortune in all the beauty that surrounded him. And the big swans swam round him, and stroked him with their beaks.

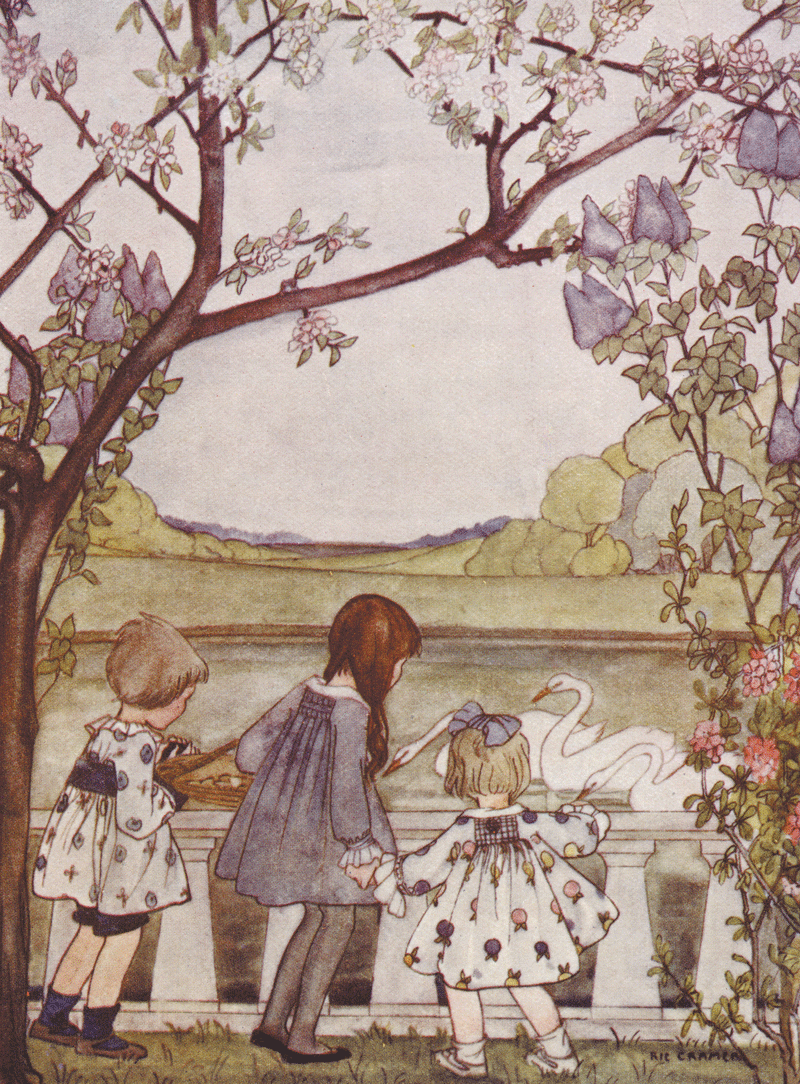

Into the garden came some little children, and threw bread and corn into the water; and the youngest cried, “There is a new one!” and the other children shouted with joy, “Yes, a new one has come!” And they clapped their hands and danced about, and ran to their father and mother; and bread and cake were thrown into the water; and they all said, “The new one is the most beautiful of all! so young and handsome!” and the old swans bowed their heads to him.

Then he felt quite shy, and hid his head under his wings, for he did not know what to do; he was so happy, and yet not at all proud, for a good heart is never proud. He thought of how he had been persecuted and despised; and now he heard them all saying that he was the most beautiful of all beautiful birds. Even the lilac bent its branches straight down into the water before him, and the sun shone warm and mild. He ruffled his feathers and lifted his slender neck, and from his heart he cried joyfully:

“Of so much happiness I never dreamed when I was the ugly duckling!”