The Elfin Hill – A Hans Christian Andersen Tale

An invitation sent by a raven, a grand banquet of frogs, and an old goblin in search of a wife.

The Elfin Hill

– A Hans Christian Andersen Tale –

Some large lizards were running nimbly about in the clefts of an old tree; they could understand each other very well, for they spoke lizard language.

“How it is rumbling and buzzing in the old elfin hill!” said one lizard. “I’ve not been able to close my eyes for two nights because of the noise! I might just as well lie and have toothache, for then I can’t sleep either!”

“There’s something going on in there!” said another lizard. “They let the hill stand on four red posts till cock-crow, to have it regularly aired, and the elfin girls have learnt new dances with some stamping in them! There’s something going on.”

“Yes, I have talked with an earthworm of my acquaintance,” said the third lizard. “The earthworm came straight out of the hill, where he had been grubbing in the ground night and day: he had heard a great deal. He can’t see, poor creature, but he understands how to wriggle about and listen. They expect visitors in the elfin hill—visitors of rank, but who they are the earthworm could not tell, and perhaps, indeed, he did not know. All the will-o’-the-wisps are ordered to hold a torch dance, as it is called; and the silver and gold, of which there is plenty in the elfin hill, is being polished and put out in the moonshine.”

“Who may these strangers be?” asked all the lizards. “What can be going on? Hark, how it hums and how it rumbles!”

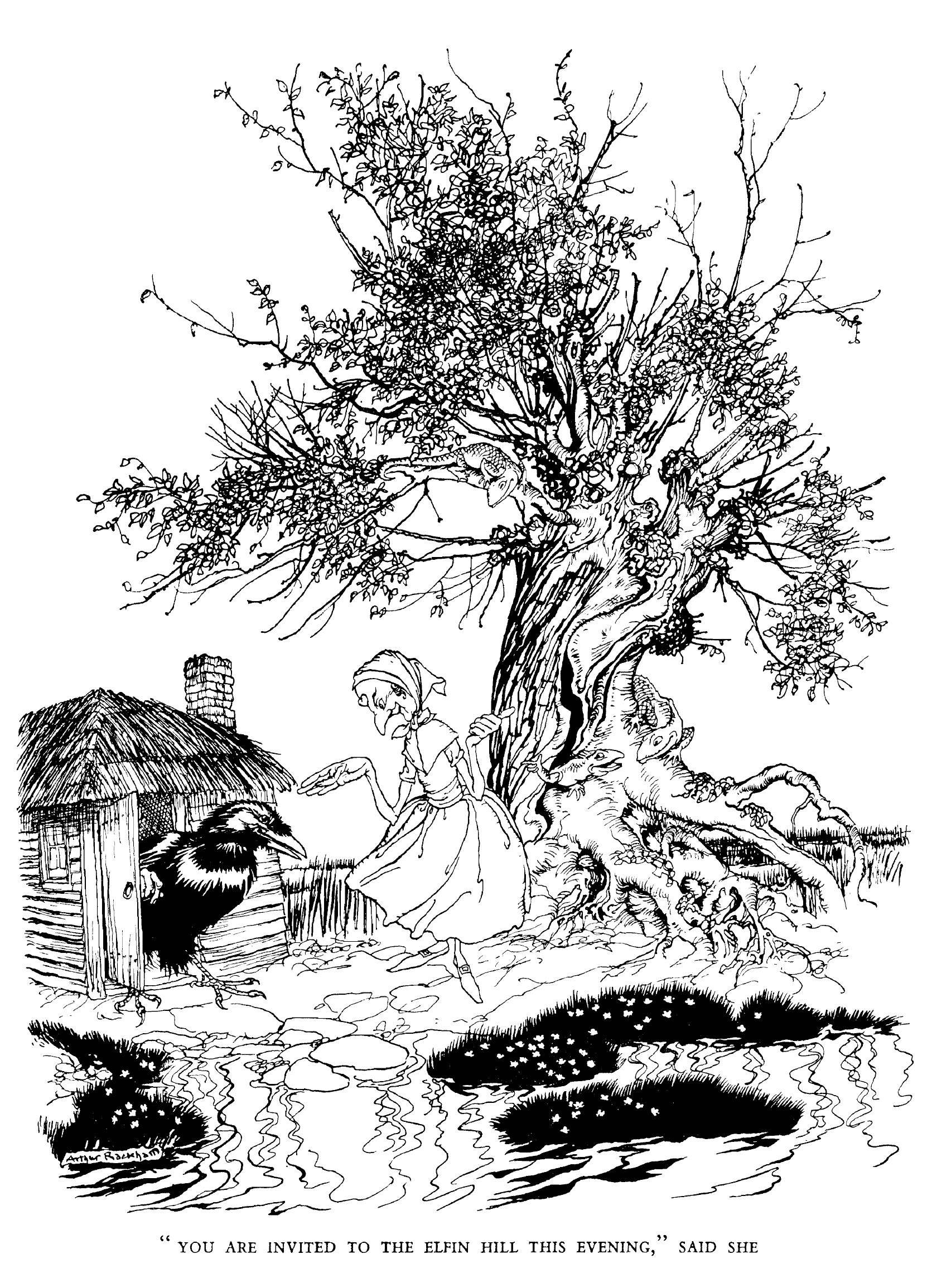

At the same moment the elfin hill opened, and an old elfin maiden, hollow at the back, but for the rest very respectably dressed, came tripping out. She was the old elfin king’s housekeeper. She was a distant relative of the family, and wore an amber heart on her forehead. Her legs moved so rapidly—trip, trip! Gracious!—how she could trip!—straight down to the moor, to the night raven.

“You are invited to the elfin hill this evening,” said she, “but will you do me a great service and undertake the invitations? You ought to do something, as you don’t keep house yourself. We shall have some very distinguished friends, troll-folk who have something to say; and so the old elfin king wants to make a display.”

“Who’s to be invited?” asked the night raven.

“To the grand ball all the world may come, even human beings, if they can talk in their sleep, or can do something in our way. But for the banquet the company is to be strictly select; we shall only have the most distinguished. I had a dispute with the elfin king, for in my opinion we could not even admit ghosts. The merman and his daughters must be invited first. They may not be much pleased to come on dry land, but they shall have a wet stone to sit upon, or something still better, and then I think they won’t refuse for this once. All the old trolls of the first class, with tails, and the wood demon and his gnomes we must have; and then I think we may not leave out the grave pig, the death horse, and the church dwarf, though they certainly belong to the clergy, who are not of our class. But that’s only their vocation; they are closely related to us and frequently pay us visits.”

“Caw!” said the night raven, and flew off at once to give the invitations.

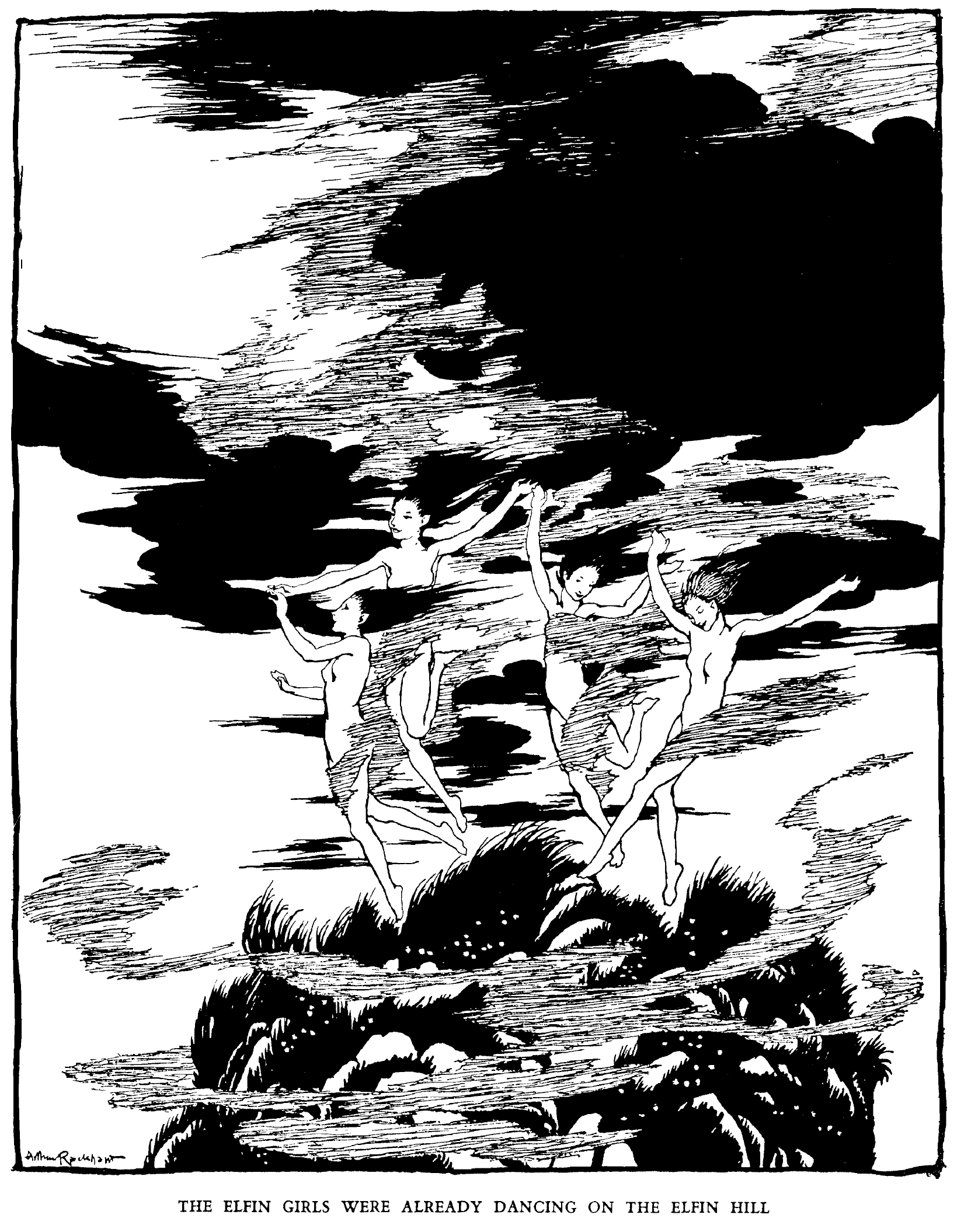

The elfin girls were already dancing on the elfin hill, and they danced with long shawls woven of mist and moonshine, and that looks very pretty for those who like that sort of thing. In the middle of the elfin hill was the great hall, splendidly decorated. The floor had been washed with moonshine, and the walls rubbed with witches’ fat, so that they shone in the light like tulips. In the kitchen plenty of frogs were roasting on the spit, snail-skins with little children’s fingers, and salads of mushroom spawn, wet mice’s snouts, and hemlock; beer brewed by the marsh witch, sparkling saltpetre wine from grave cellars—all very substantial eating. Rusty nails and church window glass were among the sweets.

The old elfin king had his golden crown polished with powdered slate pencil; it was slate pencil from the first form, and it’s very difficult for the elfin king to get first form slate pencil! In the bedroom curtains were hung up, and fastened with snail-slime. Yes, there was indeed a rumbling and jostling there!

“Now we must perfume the place by burning horsehair and pig’s bristles, and then I think I shall have done my part,” said the old elfin maiden.

“Father dear,” said the youngest daughter, “may I hear now who our distinguished guests are to be?”

“Well,” said he, “I suppose I must tell you now. Two of my daughters must be prepared to be married! Two will certainly be married. The old goblin from Norway, he who lives in the old Dovrefjeld, and possesses many strong castles on the rocky hills, and a gold mine which is better than anyone thinks, is coming with his two sons, who both want to choose a wife. The old goblin is a true old honest Norwegian veteran, merry and straightforward. I know him from old days, when we drank with one another. He came here to fetch his wife; now she is dead—she was a daughter of the King of the Chalk-cliffs of Möen. He took his wife on tick, as the saying is. Oh, how I am longing for the old Norwegian gnome! His sons, they say, are rather rude, forward youngsters, but perhaps people do them wrong, and they’ll be right enough when they grow older. Let me see that you can teach them manners!”

“And when will they come?” asked one of his daughters.

“That depends on wind and weather,” said the elfin king. “They travel economically: they come when there’s a chance of a ship. I wanted them to go across Sweden, but the old one did not like that way. He does not advance with the times, and I don’t like that.”

Just then two will-o’-the-wisps came hopping up, one quicker than the other, and so one came first.

“They’re coming! They’re coming!” they cried.

“Give me my crown, and let me stand in the moonshine,” said the elfin king.

And the daughters lifted up their shawls and bowed down to the ground.

There stood the old goblin from Dovre, with a crown of hardened icicles and polished fir cones. Moreover, he wore a bearskin and great warm boots. His sons, on the contrary, went bare-necked, and with no braces, for they were strong men.

“Is that a hill?” asked the younger of the boys, and he pointed to the elfin hill. “Up in Norway we should call it a hole.”

“Boys!” said the old man, “a hole goes in, a hill goes up. Have you no eyes in your heads?”

The only thing they wondered at down here, they said, was that they could understand the language without difficulty.

“Don’t give yourself airs!” said the old man. “One would think you were not full-fledged.”

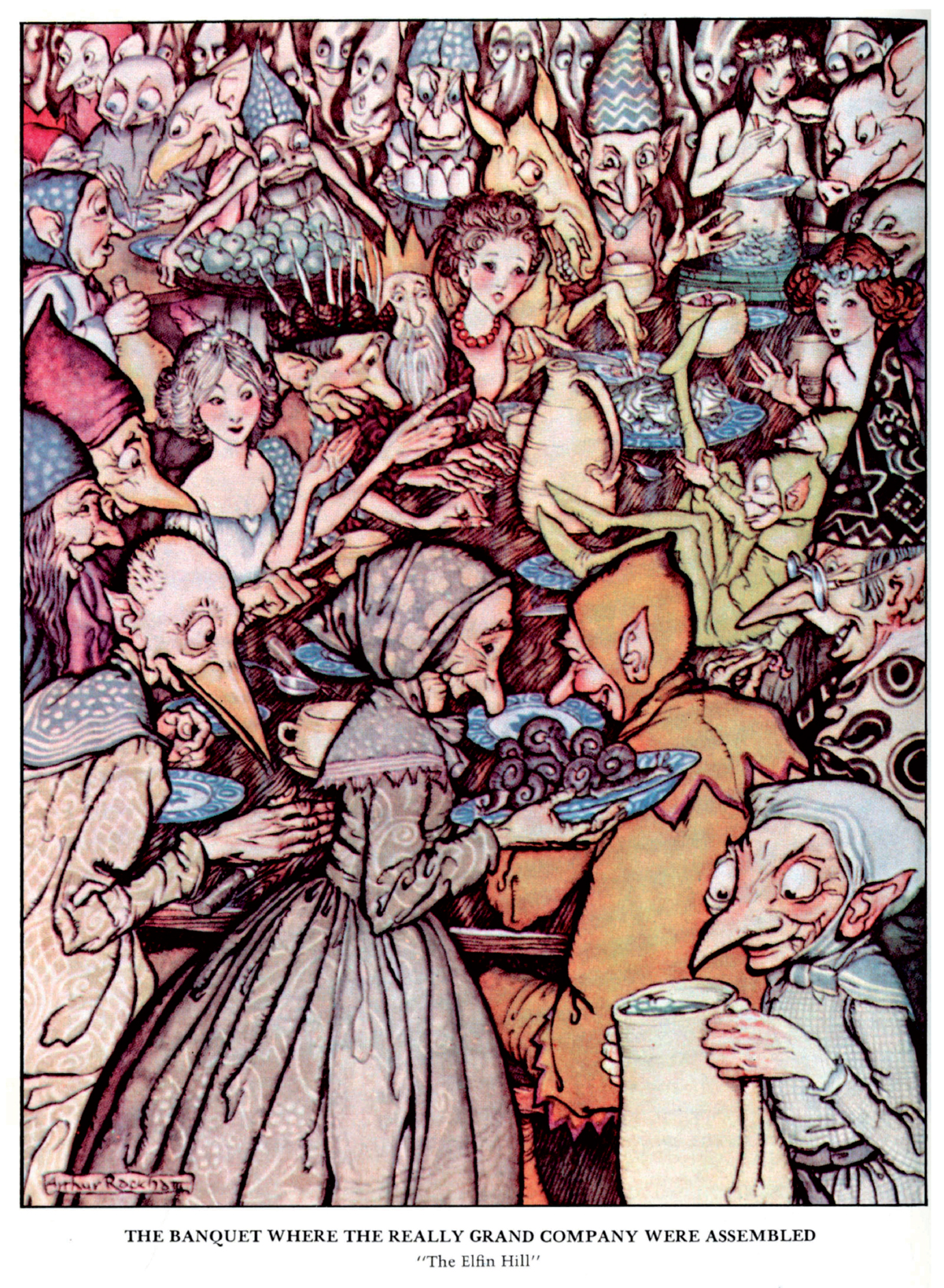

And then they went into the elfin hill, where the really grand company were assembled, and that in such haste that one might almost say they had been blown together. But for each it was nicely and prettily arranged. The sea folk sat at table in big wash-tubs: they said it was just as if they were at home. All showed good table manners except the two small Northern trolls, and they put their legs up on the table; but they thought that everything became them.

“Feet off the table!” said the old goblin, and they obeyed, but not immediately. The ladies who sat next to them they tickled with pine cones that they had brought with them, and then took off their boots to be more at their ease, and gave them to the ladies to hold, but their father, the old Dovre goblin, was quite different; he told such fine stories of the imposing Norwegian rocks, and of the water falls which rushed down white with foam with a noise like thunder and the sound of organs; he told of the salmon that leap up the rushing streams when the nixie plays upon her golden harp; he told of shining winter nights, when the sledge bells are jingling, and the lads skate with burning torches over the clear ice, which is so transparent that they can see the fishes start beneath their feet. Yes, he could tell it so finely that one saw and heard what he described. It was just as if the sawmills were going, as if the servants and maids were singing songs and dancing the hailing dance. Hurrah! All at once the old goblin gave the old elfin girl a smacking kiss! That was a kiss! And yet they were not related to each other at all!

Then the elfin maidens had to dance, first in the usual way and then with stamping steps, and that suited them well; then came the artistic and solo dance. Gracious! How they could stretch their legs! Nobody knew where they began and where they ended, which were their arms and which their legs—they were all mixed up like wood shavings; and then they whirled round till the death horse turned giddy and was obliged to leave the table.

“Prrrr!” said the old goblin. “That’s good fun for the legs! But what else can they do besides dancing, stretching their legs, and making a whirlwind?”

“That you shall soon know!” said the elfin king.

And he called out the youngest of his daughters. She was as dainty and light as moonshine; she was the most delicate of all the sisters. She took a white shaving in her mouth, and disappeared—that was her gift.

But the old goblin said he should not like his wife to possess this gift, and he did not think that his boys would either.

The second could walk beside her own self, just as if she had a shadow, and that is what the troll-folk never have.

The third daughter was of quite another kind; she had learned in the brewhouse of the marsh witch, and understood how to lard elder-tree logs with glow-worms.

“She will make a good housewife,” said the old goblin; and then he winked a health to her with his eyes, for he did not want to drink too much.

Next came the fourth elfin girl; she had a big golden harp to play upon, and when she struck the first string all lifted up their left feet, for the trolls are left-legged, and when she struck the second chord all had to do what she wished.

“That’s a dangerous woman!” said the old goblin; but both his sons went out of the hill, for they had had enough of it.

“And what can the next daughter do?” asked the old goblin.

“I have learned to love everything that is Norwegian,” said she, “and I will never marry unless I can go to Norway.”

But the youngest sister whispered to the old king, “That’s only because she has heard in a Norwegian song that when the world sinks down the cliffs of Norway will remain standing like monuments, and so she wants to get there, because she is afraid of sinking down too.”

“Ho! ho!” said the old goblin. “Is that the meaning of it? But what can the seventh and last do?”

“The sixth comes before the seventh!” said the elfin King, for he could count. But the sixth would not come out.

“I can only tell people the truth!” said she. “Nobody cares for me, and I have enough to do to sew my shroud.”

Now came the seventh and last, and what could she do? Why, she could tell stories, as many as ever she wished!

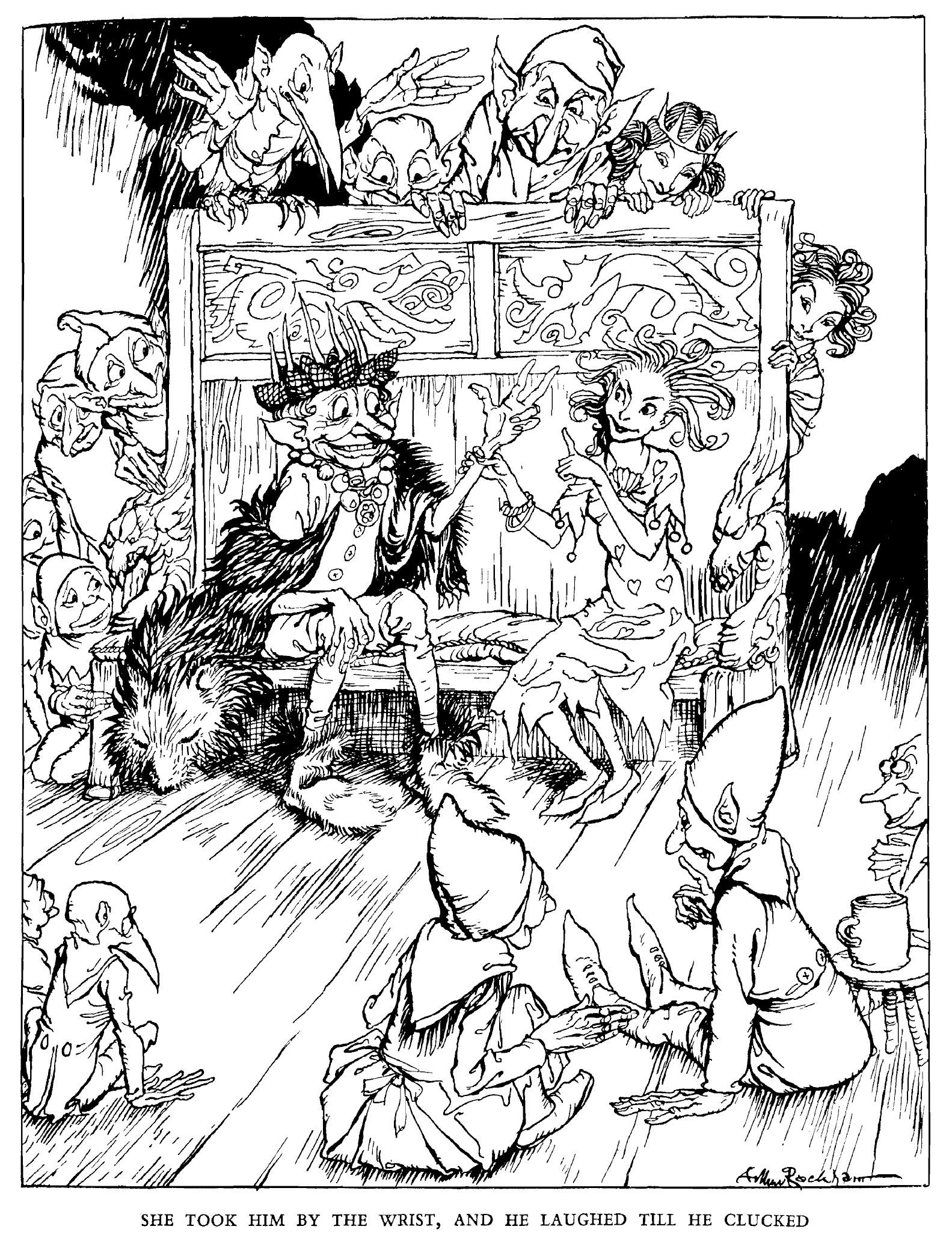

“Here are all my five fingers,” said the old goblin. “Tell me one for each!”

And she took him by the wrist, and he laughed till he clucked, and when she came to the ring finger, which had a golden ring round its waist, just as if it knew there was to be a wedding, the old goblin said:

“Hold fast what you have: the hand is yours; I’ll have you for a wife myself!”

And the elfin girl said that the story of the ring finger and of little Peter Playman, the fifth, were still to be told.

“We’ll hear those in winter,” said the goblin, “and we’ll hear about the pine-tree, and the birch, and the fairies’ presents, and the crackling frost. You shall tell your tales, for no one up there knows how to do that well; and then we’ll sit in the stone rooms where the pine logs burn, and drink mead out of the golden horns of the old Norwegian kings—the Neckan has given me a couple; and when we sit there, and the nixie comes on a visit, she’ll sing you all the songs of the saeter girls. That will be merry. The salmon will leap in the waterfall against the stone walls, but they cannot come in.”

“Yes, it’s very good living in dear old Norway; but where are my boys?”

Yes, where were the boys? They were running about in the fields, and blowing out the will-o’-the-wisps, which had come so kindly for the torch dance.

“What’s all this romping about?” said the old goblin. “I have taken a mother for you, and now you may take one of the aunts.”

But the lads said that they would rather make a speech and drink good fellowship—they did not want to marry; and they made speeches, and drank brotherhood, and tipped up their glasses on their nails, to show they had emptied them. Afterwards they took their coats off and lay down on the table to sleep, for they did not stand on ceremony. But the old goblin danced about the room with his young bride, and he changed boots with her, for that’s more fashionable than exchanging rings.

“The cock is crowing,” said the old elfin girl who kept house. “Now we must shut the shutters, so that the sun may not burn us.”

And the hill shut itself up.

But outside the lizards ran up and down in the cleft tree, and one said to the other:

“Oh, how much I like that old Norwegian goblin!”

“I like the boys better,” said the earthworm. But he could not see, the miserable creature.

* * * * *

This story was taken from the book:

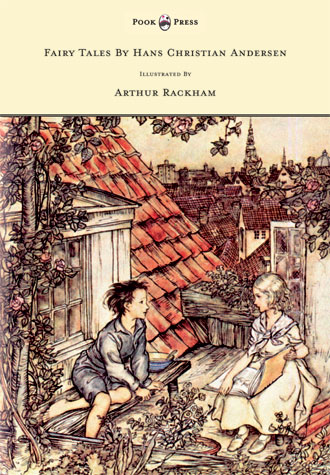

Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen – Illustrated by Arthur Rackham

This collection, Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen was originally published in 1932. It contains many of Hans Christian’s best-loved tales, and is illustrated by the charming colour plates and black and white drawings of Arthur Rackham. The stories include: ‘The Ugly Duckling’, ‘The Snow Queen’, ‘The Steadfast Tin Soldier’, ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’, ‘Thumbelina’, ‘The Princess and the Pea’, ‘The Little Match Girl’, ‘The Little Mermaid’, and many more.

More Pook Press books you might like: