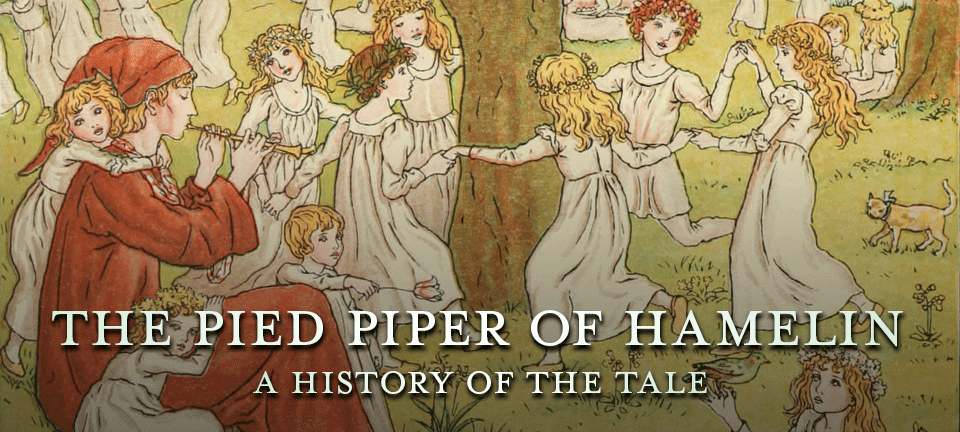

The History of the Pied Piper of Hamelin

The Pied Piper of Hamelin (known in German as Rattenfänger von Hameln) is the subject of a legend concerning the disappearance (and most likely death) of a great number of children from the town of Hameln, in Lower Saxony, Germany.

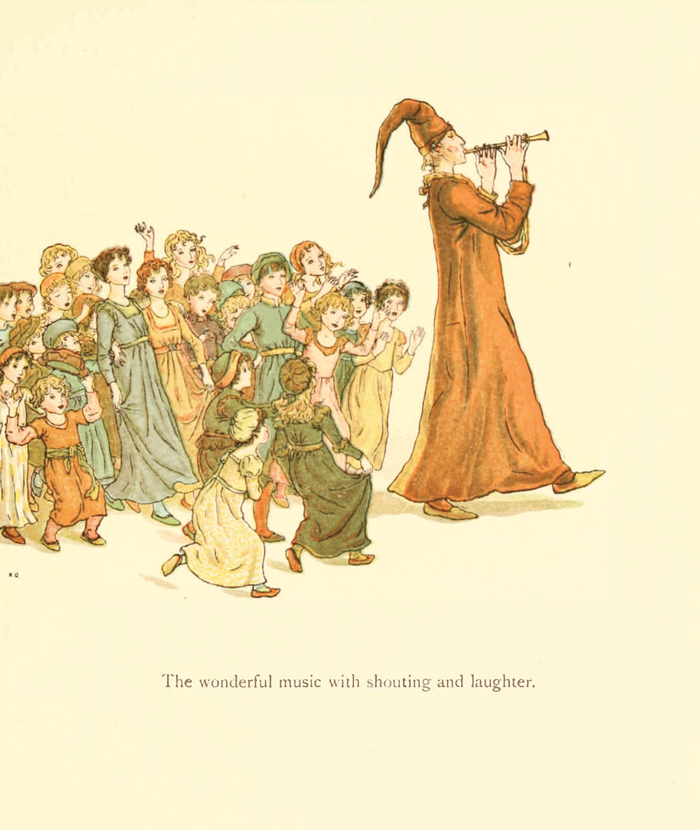

The events in question are thought to have taken place during the middle ages, and the earliest references describe a piper, dressed in multicoloured (‘pied’) clothing, leading the children away from the town never to return. In the sixteenth century the story was expanded into a full narrative, in which the piper is a rat-catcher hired by the town to lure rats away with his magic pipe. The mayor in turn promised to pay him for the removal of the rats. The piper accepted, and played his pipe to lure the rats into the Weser River, where all but one drowned.

SELECTED BOOKS

Despite the piper’s success, the mayor reneged on his promise and refused to pay him the full sum. The piper left the town angrily, vowing to return later to take revenge. On Saint John and Paul’s day, while the Hamelinites were in church, the piper returned, dressed in green, like a hunter, playing his pipe, and in so doing attracting the town’s children. One hundred and thirty children followed him out of town, where they were lured into a cave and never seen again. Depending on the version, at most three children remained behind: One was lame and could not follow quickly enough, the second was deaf and followed the other children out of curiosity, and the last was blind and unable to see where he was going. These three informed the adults what happened when they came out from church.

This version of the story spread as folklore and has also appeared in the writings of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the Brothers Grimm and Robert Browning, among others.

The earliest known record of this story is from the town of Hamelin itself depicted in a stained glass window created for the church of Hamelin, which dates to around 1300 CE. Although it was destroyed in 1660, several written accounts have survived. The window is generally considered to have been created due to very real memories of a tragic historical event. Hamelin’s town records even start with this event – in an entry from 1384 which states: ‘It is 100 years since our children left.’ The oldest written account of the story as a whole comes from the Luneburg manuscript (c. 1440 – 50), which stated:

In the year of 1284, on the day of Saints John and Paul on 26th June, by a piper, clothed in many kinds of colours, 130 children born in Hamelin were seduced, and lost at the place of execution near the koppen.

Although research has been conducted for centuries, no explanation for the historical event is agreed upon. In any case, the rats were first added to the story in a version from 1559, and are absent from earlier accounts. Theories have been proposed suggesting that the Pied Piper is a symbol of the children’s death by plague or catastrophe. Other theories liken him to figures like Nicholas of Cologne, who is said to have lured away a great number of children on a disastrous Children’s Crusade (a disastrous Crusade by European Christians to expel Muslims from the Holy Land said to have taken place in 1212). The current theory, generally accepted by scholars and historians, ties the departure of Hamelin’s children to the Ostsiedlung, in which a number of Germans from the Holy Roman Empire left their homes to colonize Eastern Europe.

The ‘natural causes’ theory is perhaps the most prevalent explanation for the children’s disappearance in the story. Analogous themes which are associated with this theory include the ‘Dance of Death’, Totentanz or Danse Macabre, a common medieval trope. Some of the scenarios that have been suggested as fitting this theory include that the children drowned in the river Weser, were killed in a landslide, or contracted some disease during an epidemic. Added speculation on the ‘migration theory’ is based on the idea that by the thirteenth century, the area had too many people resulting in the oldest son owning all the land and power (‘majorat’), leaving the rest as serfs. It has also been suggested that one reason the emigration of the children was never documented was that the children were sold to a recruiter from the Baltic region of Eastern Europe, a practice that was not uncommon at the time.

Whatever the reality of events, there have been numerous retellings of this most mysterious of stories. Somewhere between 1559 and 1565, Count Froben Christoph von Zimmern included a version in his Zimmerische Chronik. This appears to be the earliest account which mentions the plague of rats. The earliest English account is that of Richard Rowland Verstegan (1548 – 1636), an antiquary and religious controversialist of partly Dutch descent, in his Restitution of Decayed Intelligence (1605). The phrase ‘Pide Piper’ occurs in his version and seems to have been coined by him.

The story is given, with a different date, in Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy of 1621, where it is used as an example of supernatural forces: ‘At Hammel in Saxony, ann. 1484, 20 Junii, the devil, in likeness of a pied piper, carried away 130 children that were never after seen.’ It is also the subject of a poem written by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in 1803, later set to music by Hugo Wolf (an Austrian composer of Slovene origin).

Jakob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm, known as the Brothers Grimm, drawing from eleven sources, included the tale in their collection ‘Deutsche Sagen’, first published in 1816. According to their account, two children were left behind as one was blind and the other lame, so neither could follow the others. The rest became the founders of Siebenbürgen (Transylvania). More recently, the tale has been the subject of a long poem by Marina Tsvetaeva (1892 – 1941; a Russian and Soviet poet), entitled ‘The Rat Catcher’, in which rats are an allegory of people influenced by Bolshevik propaganda. There was also a short film produced by Walt Disney Productions (released on 16th September 1933), as part of their ‘Silly Symphonies’ series.

As a testament to this story’s ability to inspire and entertain generations of readers, The Pied Piper of Hamelin continues to influence popular culture internationally, lending plot elements, allusions and tropes to a wide variety of artistic mediums. The tale has been translated into almost every language across the globe, and very excitingly, is continuing to evolve in the present day.

SELECTED BOOKS