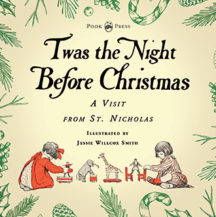

Father Christmas at Home

A determined young girl, a mysterious reflection and a trip to Christmas Land.

Father Christmas at Home is the tale of a young girl who travels to Santa Claus’s home to ask him an important favour. Here Eva discovers the secrets and mysteries of Santa – where the presents come from, and where they are stored – how they are packed and how they are delivered while we all asleep in our beds. She also learns an important lesson, one which is of service to man, and woman and child as well.

This story can be found in The Rainbow Book – Tales of Fun & Fancy. A wonderful collection of stories for children, written by M. H Spielmann and illustrated by some of the greatest artists of the Golden Age of Illustration. This story is illustrated by Arthur Rackham.

Father Christmas at Home

A Christmas Story

TWILIGHT

IT was afternoon on a cold December day. Eva, all alone in the schoolroom, sat down on the hearthrug and looked thoughtfully into the fire. She was, however, not quite alone, for her tiny Yorkshire terrier sprang on her lap, and after turning round and round, pawing at her frock as though to make a comfortable hollow, settled cosily down.

“Dot,” she said, smoothing the hair back from its eyes, “I’m very miserable. To-morrow is Christmas Eve, and every one is happy except me, I’m in trouble again. Somehow, I’m always in trouble—I’ve spoilt my velvet frock washing your feet—and you didn’t want them washed, did you?” The Honourable Dot—to give it its full title—looked desirous of forgetting the incident, then licked her hand as a reply seemed expected.

“Perhaps if I had some brothers and sisters they’d get into mischief sometimes, and it wouldn’t always be me.” Dot paid no heed to her grammar, was bored, and sighed heavily.

“I really didn’t mean it when I said, ‘I gloried in being naughty.’ Don’t snore, Honourable! There’ll be complaints from next door.”

It was curious, but Eva was having remorse, brought on by all the talk of Peace and Goodwill which was in the air. “I’ve tried things before,” she muttered; “but I know what I’ll do this time,” she exclaimed, “I’ll give a cot to a hospital!”

The little dog growled a protest as she suddenly got up from the floor. Eva counted the money in her money-box. “I’ve five shillings all but three farthings. I’m sure that is nothing like enough!” she mused. “It must cost at least a million sterling pounds!” Tears came into her eyes, but they flowed down on to a smile, as she thought of some one who always managed to do kind deeds and who might help her. Father Christmas! Eva thought of asking no less a person than Father Christmas himself to advise her. But how to find him and get a nice quiet chat with him was the difficulty. That he would come to her on Christmas Eve she had no doubt, as he never forgot her; but she had only managed to be awake and see him once, a long time ago, and then she but got a glimpse of him, for he rushed out of her room as though in a terrible hurry.

Dot’s little mistress slept badly that night; she was racking her brain as to how she could manage to remain awake so as to see Father Christmas when he came, and then how she could coax him to stay for a talk—for she knew quite well how busy he must be when he was on his rounds.

The following afternoon, during a general rummage that was going on to find tiny candles and coloured glass balls that were over from last year’s Christmas tree, Eva picked up a scrap of printed paper, which had come out of an old cracker. She took it upstairs to her favourite spot on the hearthrug, and read it aloud to Dot:—

“Father Christmas sends this note

From out his mansion by the moat,

To all who live on land and sea,

To honour Christmas Day with glee—

Inviting them to pass his way,

With glee to honour Christmas Day.”

Eva flushed with excitement. “Why, it’s a message from him!” she cried. “It’s some kind of invitation!” and she gave Dot such a squeeze of delight that the little creature squeaked shrilly, scurried off, and laid low under the table.

She thought and puzzled and pondered over the lines she had just read. At last she grasped their meaning. “Of course! How simple, after all!” she concluded. “He lives at some moated house, and I must go to him, not wait for him to come to me. He always comes down the chimney—that’s the way I must go up!”

Eva didn’t hesitate a moment. The opportunity had come for which she longed. She ran downstairs into the large, old-fashioned hall, which was overheated as usual, by the hot-air pipes, for the huge chimney-place was too much of a curiosity ever to be used. Here, she felt sure, was the starting-point of her adventure.

Luckily no one was about. It was windy when she looked up the great chimney, so she took her long, fair hair, and made it into a loose plait in order to keep it from blowing about her face. Then she prepared to start and secure the first footing.

Eva had never been up a chimney before, and when she began climbing she was quite surprised to find how nice and clean it was, with steps, and all white tiles. She toiled up, and up, and could see blue sky and fleeting white clouds above. After a time she stopped to rest in a little recess in the chimney side. When she started climbing again, the blue sky faded away, twilight came on, and in this very, very long chimney the light became quite dim.

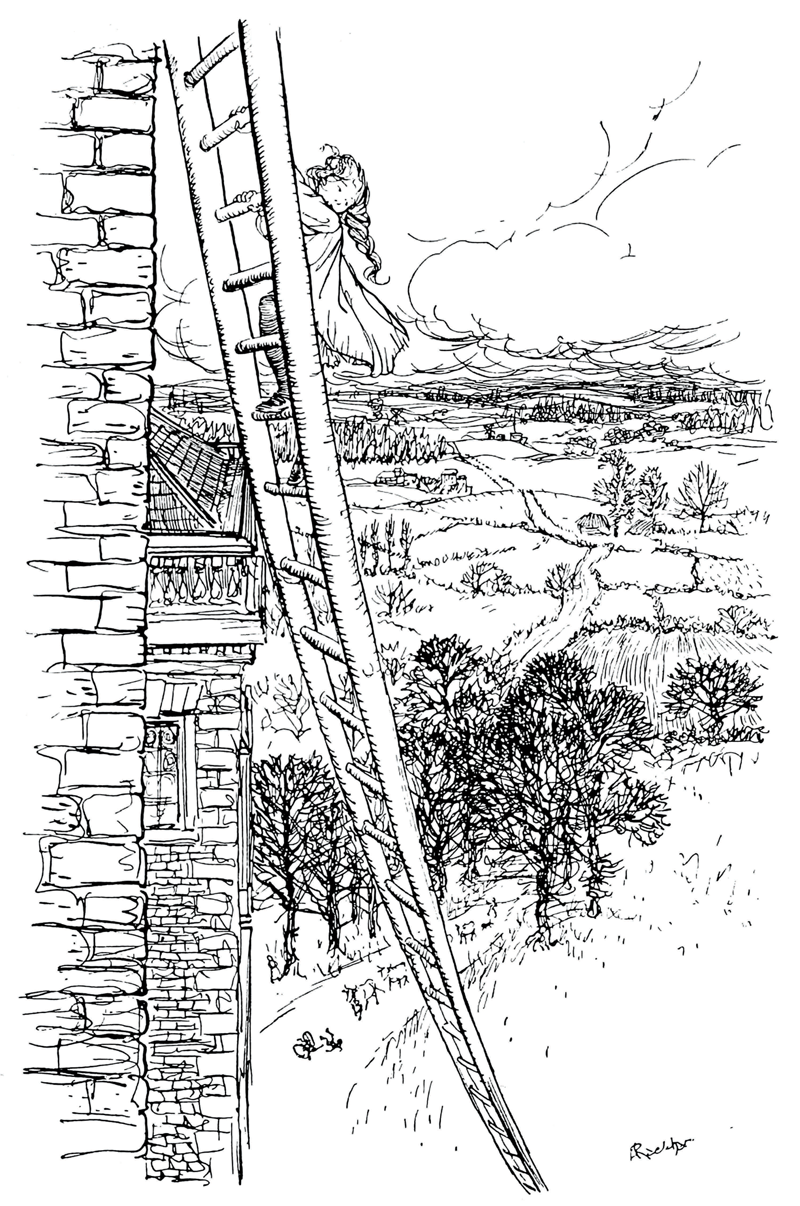

Very soon, however, she felt with a little thrill of pleasure the keen air all around her head and shoulders, and she knew she had come to the top. Fortunately there was a ladder—already placed for Father Christmas to mount—and down that she went, looking below all the time so as not to make a false step. It was a very, very long ladder indeed, and Eva began to think she would have to go on stepping down forever, when at last she found herself on the ground again—in a country field with hoar frost stiffening the blades of grass, across which she ran straight ahead as hard as ever she could go.

STARLIGHT

Once only did she halt by the side of a lane to consider what she should do if she couldn’t find her destination after all. Two robins alighted in front of her, hopped about, and fluttered forward; they were so persistent that they interested her and she followed them. They flew along a side path, and Eva ran after them—ran till she arrived eager and breathless at a wooden bridge, and found that she was in a park; that above her was the dark vault of heaven decked out in all its diamonds; that the bridge led across a moat; and that in front of her was a splendid old country mansion brilliantly lighted up, where the robins alighted on a window-sill, and paying no further attention to her, busied themselves with crumbs.

Then Eva advanced, almost in spite of herself, went up the front steps, and standing on tiptoe, lifted the knocker and let it fall. The knocker resounded for a while musically, like a peal of bells; when they ceased, the door opened, and a very ancient man confronted her. He was tall and thin and bent, and was dressed in draperies, with bare legs, and he had a funny little curl in the middle of his bald forehead.

“Is Father Christmas at home, please?” faltered Eva.

“Yes, little Madam,” came the reply. “Do you want to see him? Really? But you will be astonished—I warn you. Aren’t you frightened?”

“Not a bit,” replied Eva.

“Brave little girl!” said the very ancient man. “Come in!” and he ushered her into an old oak-panelled room. It had a delicious sense of comfort, and a delight about it which, for the moment, she didn’t try to define. Her attention was attracted by catching sight of what she thought was her own reflection in the large mirror against the wall—it was a little girl who came in at the same time, and was of exactly her own height. As she looked closer she saw that the other child was uglier than herself, unkind in expression, slovenly in appearance, and tried to hide herself, rather, in the dark corner where she remained. And Eva, in the novel surroundings, soon forgot all about her.

At the far end was a great log fire, and near it a huge arm-chair, in which sat a stout, healthy, red-faced old gentleman warmly wrapped in a crimson dressing-gown; he was leaning back, thinking or dozing. Eva advanced with soft steps. She was full of eagerness and excitement, for she recognised the white-bearded, handsome old face at once from the many coloured portraits she had seen. It was Father Christmas himself! Eva never knew what impelled her to do it, but when she got close to him she simply threw her arms around his neck and kissed him.

“Bless my soul!” exclaimed Father Christmas, starting; and catching her up, he seated her on his knee. He recognised her at once. “How you’ve grown since last year, Eva!” and he looked at her with beaming eyes. “I suppose you know you’re trespassing? and the penalty is forty crackers or a kiss!” And he chuckled and laughed so merrily that she felt quite comfortable, finding trespassing a very pleasant occupation, and wasn’t a bit alarmed at the penalty.

“And what brings me this honour?” he continued.

“Good evening, Father Christmas,” spoke up Eva quite boldly. “I’m afraid I disturbed you.”

“Oh yes, you’ve disturbed me all right,” he replied briskly, “but I was only resting a little after my labours before going on my rounds to-night.”

“What labours?”

“Toys. Toys and sweets. I’ve been making toys and things all the year through, and have only just got them finished in time. I love making crackers, too; I spend all my evenings writing mottoes for them.”

“I found your invitation, Mr. Christmas.”

“Bless me! did you now? Ah!” He stroked his beard thoughtfully for a moment and remained silent. Eva looked about her in amazement.

“Those are all secrets!” he observed after a time. Father Christmas included with a sweep of the arm the toys which were everywhere about—hanging from the ceiling, lying about on the tables and sofas, standing as ornaments on the mantelpiece, filling the shelves of the bookcases, peeping from behind the glass cabinets—toys wherever one looked.

He arose, and taking her by the hand, led her round to enjoy the pretty sight; and paying no attention whatever to the sullen little girl in the corner, he asked Eva if she would like to see around his domain. “Oh yes, yes,” she cried. She quite appreciated the special honour that was being done her.

“They’ll be coming in here soon to pack,” he added. “I’m going to leave all these secrets myself at their destinations.”

There was a tremendous bustle going on at the rear of the premises, where a whole army of packers, carriers, postmen, and porters were hurrying about letting down toys from the loft, packing them, labelling them to places far and wide; loading them on huge vans which came rumbling in and out of the courtyard with cracking of whips, and parting shouts of “Good luck!”

Superintending the arrangements, walking to and fro, was the very ancient man. He was so alert, and always on the spot where wanted, yet Eva was thinking his age must at least be two hundred, when Father Christmas said kindly: “My dear, this is my father—he is known as Father Time, and you have known him without having really met him face to face before.”

“I didn’t recognise him, and I didn’t know he was your father, sir,” she whispered.

“Why, yes. Don’t you know that my full name is Christmas Time?”

“Of course it is,” she exclaimed with a laugh.

The next visit was through a covered way to the printing works—where the mottoes and “directions” for toys and Father Christmas’s visiting cards were printed. These cards were all different in design, and each was a beautiful picture stamped with his name, and his own motto, “Peace and Goodwill.”

Behind was the sweet factory, with its tempting packets and muslin stockings of all sizes full of sugar-plums. But, as Father Time appeared, Father Christmas whispered that he feared they must not linger, and led the way up a spiral staircase in order to enable Eva to have a peep into the toy-loft, where men were letting the toys down into the busy yard below. How she would have loved to stay longer in each delightful place, but without a murmur she followed her guide below and back to the oak-panelled room. It looked so bare and different without the toys—much like any ordinary room.

“And now, my dear,” he said, “you must excuse me for a short time, as I must go upstairs and get ready.”

“Please, ought I to be going?” she asked politely.

“No, no. Not yet.” And he went away, up the grand staircase, to his bedroom. There he took from the drawer his scarlet fur-lined cloak and hood with wide swansdown trimming, which had been put away in lavender, chose his thickest top-boots, and humming a song, proceeded to array himself for the long, cold journey in store for him that night.

Meanwhile, the moment he left his little visitor downstairs, the strange-looking child approached her.

“What’s your name?” asked Eva pleasantly.

“Eva,” came the surly reply.

“Why, that’s my name!”

“Of course. I know you, I know you through and through—good and bad—and I wish I didn’t.”

“You’re a horrid story-teller,” said Eva angrily.

“Supposing I am! It’s easier to tell stories than to tell the truth. Saves a lot of trouble. Besides, it’s nice. You know that as well as I do.”

Eva would have liked to deny it, only she felt too scornful. “Saves trouble?” she said to herself. “Makes trouble.” But she flushed as she remembered she had once thought that too, but only for a moment; and she was ashamed of it now. She was ruffled and uncomfortable at the proximity of this horrid girl, who now said slyly: “Look over there in that cupboard, there’s a doll that has been forgotten. I want it, and I’m going to take it and hide it under my pinafore.”

“You mayn’t—you mustn’t!” cried Eva. “It would be stealing.”

“I don’t care. Father Christmas won’t know.”

“Yes, he will. I shall tell him!”

“Then I’ll say it was given to me.”

“You horrid girl! You dreadful story-teller!”

“Don’t be silly. What does it matter telling stories and stealing, so long as you’re not found out?”

“It’s just as bad if you’re not found out. But you are bound to be found out,” cried Eva, in horror and disgust as she saw her approach the coveted treasure. “I tell you, wicked people are always found out; they never escape unpunished.”

“I want it, and I’m going to have it.”

“You mustn’t. Come away—you shan’t!” shouted Eva, running after her; and she seized her by both wrists. “Come away! Oh, do come away!”

“You fool! leave me alone. Get away!” and with a scoffing laugh the girl shook herself free, sprang on a sofa, opened the cupboard, and stretched out her hand.

Without a word Eva threw herself upon her, slammed-to the glass door, and in the struggle they fell together on the floor. There was a crash of broken glass, and through the noise Eva heard the voice of her opponent saying faintly: “Let me go! You have won!”

When she got up, carefully shaking the bits of glass from her frock, and looked round, the horrid little girl had disappeared. The next moment her host stood in the doorway with a curious smile on his face.

“I’m going now,” he said; “will you come?”

“Oh, please, Father Christmas,” exclaimed Eva ruefully, as she looked at the glass on the floor, “do wait! I want to explain something—I——”

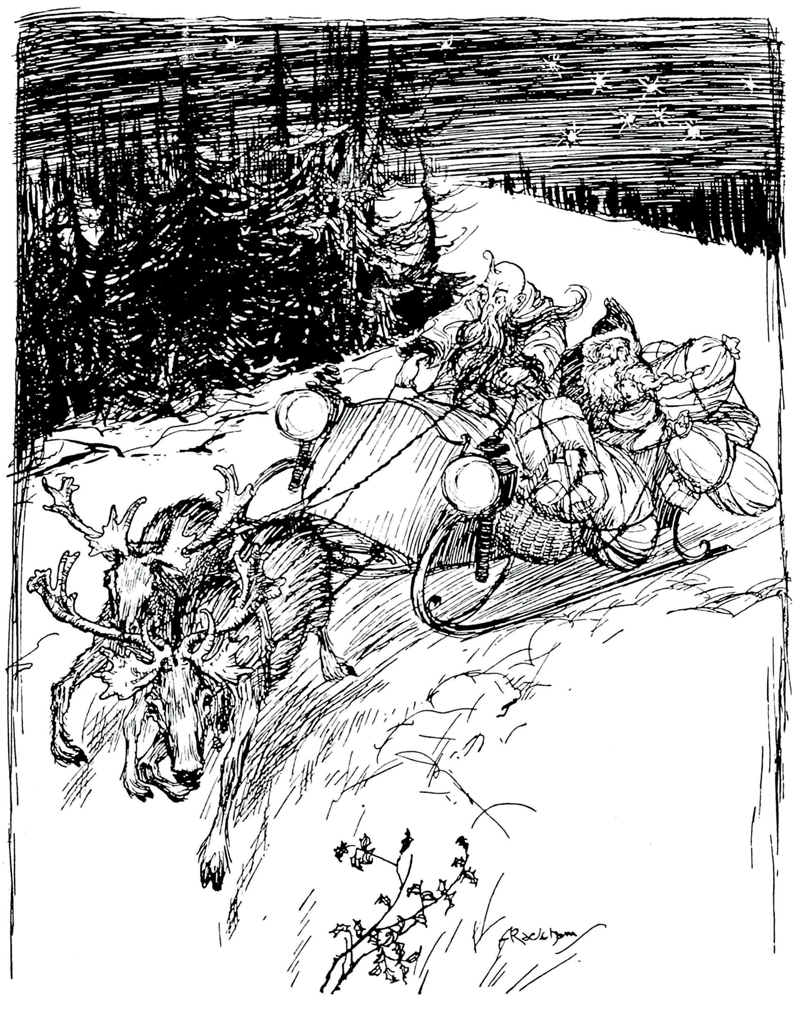

“I can’t keep my father waiting,” he answered gently. She followed him to the front door. There in the frosty night a beautiful sledge was in waiting, hung with baskets and sacks overflowing with toys and sweets. Father Christmas took his seat and beekoned to Eva. To her joy he lifted her on to his lap and wrapped his great coat about her. Father Time, who was on the box, shook the reins, and the two reindeer, impatient to be off, sped rapidly away amid the jangling of bells, carrying the travellers over the bridge, through the park, past holly and fir trees all powdered with glistening frost, out over the country into the bright, crisp night.

Father Christmas at Home Arthur Rackham

MOONLIGHT

There was Eva with Father Christmas, all snug amongst his soft furs, on his rounds. “Why do you take some toys yourself,” she asked, “and send others away in the great carts?”

“Those in the carts are for my export and wholesale trade—shops, and so on; these I take are for my special favourites. You’re on my list, my dear, you know.” Eva’s heart was full of tenderness and pride, but tears were in her eyes as she said, peering appealingly into his kind face—

“May I whisper something?”

He bent his head—and she whispered.

“Bless my soul!” was all Father Christmas replied, but he looked very pleased and jolly.

“And I should like to pay for it,” continued Eva; “I’ve got five shillings all but three farthings.”

“Never mind about that, my dear.”

“But I’m sure I ought,” she replied dubiously. “Dear Father Christmas, you are always doing kindnesses; could you tell me how to do something like giving a cot to a hospital, or a free library, or something? That’s what I really came to ask you about, only I forgot it until now. I’m so often in trouble, and I’ve so often tried to do some good, but it doesn’t come off somehow,” and she sighed.

“What you ask me is a secret,” he answered. “Some people are quick to find it out for themselves. Some people never find it out. But I will tell it to you, dear, because I know that by to-morrow you will be on the high road to guessing it. It is this: You need not give things. You needn’t try to be good. Try only not to be troublesome. If you are sweet, and gentle, and kind, you give happiness—not only do you give it, but you can then only find happiness yourself.” Somehow, it didn’t sound a bit like a sermon; it was more like being told the delightfully easy answer to a difficult sum. Eva nestled closer to her dear old friend as she listened—it was all so peaceful, reassuring, and soothing.

The moon was shining down on the sledge and its strange occupants, and Eva was just going to ask if he could tell her who the other little girl was, and all about her, when she felt her arms were being disengaged from where they clung about him, and she found herself gently deposited on firm ground, and alone.

The Honourable Dot barked with delight because it was Christmas Eve, and it was going with its little mistress to dine downstairs; and very joyful and succulent the event proved to be. Not long after, when it was fast asleep in its basket, Eva was sitting up in bed waiting anxiously to receive the visit of her recent host. Father Christmas had done her so much good, and she wanted to tell him so, as she had had no opportunity of doing before.

She was dropping asleep in that attitude, when she heard a slight noise. Immediately she started up, and clutching tightly at a rapidly retreating figure, she laughed aloud to find she had succeeded in catching Father Christmas, who, mildly yielding to her entreaties, sat down by her side.

“I have wakened you,” he said regretfully.

“Oh no, I was waiting for you.” And she told him about the happy time she had spent with him, and thanked him nicely. “What a dreadful little girl that other Eva was!” she concluded. “Who was she?”

“Ah,” said Father Christmas very quickly, “she is what you might be were you to give way to bad feelings. I wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year, my dear!” and without explaining further he kissed her and rapidly withdrew on his business.

DAYLIGHT

Outside the uncurtained window the sun was shining. Snow had been falling softly, and was piled high on the sill. And over the hushed landscape from the far distance the Christmas bells were ringing. Eva joyfully hugged a large doll, which she had found asleep on her pillow.

It was only later, when she thought over past events in detail, that it appeared to her, though she had not paid attention to it at the time, that Father Christmas seemed ill at ease when he was her visitor—perhaps it was because he was in a hurry. Somehow he was different from the stout, merry-faced old gentleman she had been to see; he had strangely shrunk to nearly as thin as her own father, and as pale, comparatively, which she thought very odd.

And when she looked up into that wonderful and mysterious old chimney again, she saw that it was all dark and black, and as uninviting as any ordinary dirty old chimney; so that it was quite hopeless for her ever to venture up it again to find old Father Christmas “At Home.”